Southern Los Padres Trails Guidebook

Walk This Way

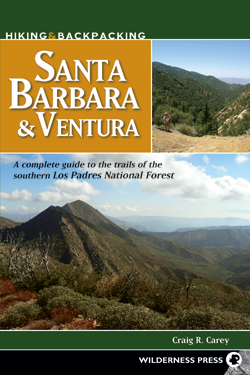

Craig Carey’s Hiking & Backpacking Santa Barbara & Ventura is a fine new guide to enjoying our beautiful local environs. Subtitled A complete guide to the trails of the southern Los Padres National Forest and reasonably priced by Wilderness Press, Carey achieves his stated goal to describe most of the great trails in the Santa Barbara, Mt. Pinos, and Ojai Ranger Districts. He covers almost 100 paths, and notes that since he offers trail descriptions from point A on the trail to point B, the hiker has the freedom to vary or alter the trip at anytime. I have found the best use is to create my own alternative trips, working off some of his suggestions.

With over 400 information-packed pages, this dense paperback covers a quite an area, has a fine index, and boasts pertinent black-and-white photos to assist the hiker in the field. Carey includes easy dayhikes and strenuous one-day killers, as well multi-day backpacks spanning over 20 miles. His 25 detailed topo maps help greatly, especially when you are undertaking a new hike solo based entirely this book’s data.

Like many backcountry guys, I’m especially interested in the federal wilderness areas within the almost two-million-acre national forest. There are five of these primitive areas near urban denizens of Santa Barbara. In order of beauty and proximity: San Rafael Wilderness, Sespe Wilderness, Chumash Wilderness, Matilija Wilderness, and Dick Smith Wilderness. Carey covers them all, and offers you many intriguing ideas for deep backpacks into these local wildlands.

The Los Padres is a threatened national treasure since, unlike other national forests, some of it contains serious mineral and oil resources. Drilling occurs on about 15,000 acres currently. Some of the issues over twisted jurisdiction between oil interests and the Forest Service (Dept. of Agriculture) result in restricted access to our own national heritage. Carey carefully writes about this striking juxtaposition of industry, land management, and environmental preservation interests, stating that the wrangling is “leaving some historically accessible sites in a legal limbo and often restricting availability to the public.”

A case in point is how my guru Franko and I used to backpack the more beautiful “backdoor” trail to Painted Rock out in the Cuyama, but now oil industry boys have illegally closed to the public the entry point for the old Bullridge Trail. Today I must go in by the seven-mile Sierra Madre Ridge Rd. via McPherson Peak.

One reason I’ve been writing this column is to attract more Santa Barbarans — with their children! — into these incredibly compelling and reasonably remote wilderness zones. We don’t need to read Richard Louv on “nature-deficit syndrome” or listen to other environmental activists on the benefits of the wild on the human psyche: Just go out there, and be prepared. I’ve been hiking in these five federal wilderness areas since 1971, often taking children, and have witnessed the impact on kids’ faces again and again.

With Carey’s tome in hand (I usually just photocopy the page I need from it, or sketch it on my own pad), we can explore coniferous glades at 9,000 feet (Mt. Pinos), scrabble across the barren and beautiful Hurricane Deck, scramble along lush riparian corridors like the Sisquoc or Sespe, and amble on easy daytrips up the Santa Barbara front-country. He details some deep backcountry routes you would be very hard-pressed to figure out on your own. He also turns you on to some glorious waterfalls, and backcountry secrets you would need 20 years to discover yourself.

Where I was able to check Carey myself, the book is generally quite accurate. If I wanted to demonstrate my thorough perusal, I could tell you that there is no longer a waterpipe there at Mission Pine Springs (pg. 147) though the spring flows as copiously as ever. You might want to know if Little Pine Spring “is usually a reliable source of water” as Carey states (p. 151), and the last two times I checked in 2012 it was not flowing, and the stock trough there is now broken. (But the 2007 Zaca Fire did miraculously miss the site, the wooden table is there, and there’s a flat place to sleep on the green.)

On my miserable last day of a recent 39-mile Mission Pine Ridge backpack, as I straggled out under my own power after getting off trail near the 40-Mile Wall, I perhaps could have gotten water at this Little Pine Spring but I didn’t have Carey’s book telling me it was usually reliable. However, on an earlier April 12 backpack, I had checked out Little Pine Spring and it was dry.

At the same time, Carey is very accurate about the way the Zaca Fire destroyed the Santa Cruz Trail heading in toward Santa Cruz Camp, a mile or so beyond the Little Pine Spring spur, and writes, “another stretch of trail often brushed-over in the years since the Zaca Fire” (p. 151).

This detailed compendium also includes permit information, trailhead directions, campsites, and waypoints, along with all the clear maps. He utilizes GPS (Global Positioning System) coordinates in the trail descriptions, and UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator) coordinates, which I believe most GPS units will support.

Readers might like the idea of a thick paperback with masses of data all in the hand. Carey is correct that the old 1974 Marty Hiester/Ray Ford Trails of the San Rafael Wilderness, the 1981 Dennis Gagnon Exploring the Santa Barbara Backcountry, and the Boy Scouts of America’s A Camper’s Guide to the Tri-County Area (I still use the Burtness 4th ed.) are badly outdated. Inaccuracies could lead to dismal results for an unwary backpacker deep in the wild.

In a recent interview with Matt Kettmann about this book, Carey responded to Kettmann’s query “Do you think there’s a resurgence in backpacking?” with a strong yes. I very much want to agree with Carey, but my limited experience is a strong no. In seven recent backpacks since June 2011, many written up as columns in this space, I rarely observed another car at the trailhead. On most of these backpacks (not dayhikes), we usually encountered zero or one or at most two fellow maniacs. It requires a major act of will to drive out there, away from our glorious sea, the foaming strand, all the art and music and culture of our little coastal town.

However, readers should consider Carey’s three reasons to get into backpacking, all reasons I have also expressed: 1) These areas are relatively accessible to all of us; 2) It’s a terrific way to get into shape; 3) It’s an easy way to get out with the kids. Nature deficit syndrome is a fancy way to say we Americans are losing touch with the outside world, the vast and beautiful nature zones right here behind us in the Santa Barbara front country. Worse, we’re letting this happen to our children.

Buy this book, purchase copies of Bryan Conant’s two splendid maps, outfit yourselves properly, and head for the hills with your family!

In Santa Barbara, you can pick up a copy of Hiking & Backpacking Santa Barbara & Ventura by Craig R. Carey (Wilderness Press, 2012, $18.95) at Chaucers Books.