Living in Two Worlds

Wounded Marines and Me

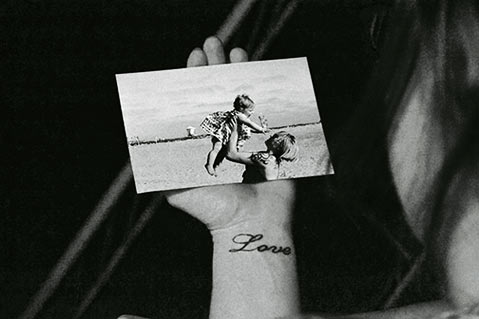

I live in two worlds

My first world, the “real world” for me, is with my family at our home near the beach in Santa Barbara. The “other” world is MCB Camp Pendleton, at the Wounded Warrior Battalion – West where I teach injured Marines photography. These two worlds could not be more diverse!

Arriving at the battalion at the beginning of my workweek or returning to our home at the end of my week sometimes seems like an out-of-body expedience. I’ve had these experiences before: when I’ve been abroad for a while or am returning to an environment I haven’t visited for a long while. But it’s always the same. It’s familiar, slightly uncomfortable, but totally different and the same, all at once. One might call these moments a déjà vu moment, that “all over again” feeling.

It might possibly be that living and working with the Marines, wounded and staff alike, on a very active military base, explosions and kabooms included, armored vehicles all over the roads, and the constant whoop-whoop-whoop of the attack helicopters overhead, might have something to do with the intensity of my days at the Marine Corps base.

The base itself is home to tens of thousands of very butch young men and women in camouflage uniforms, which can be very intimidating to a “socialist, pacifist, draft-dodging leftover hippie” like myself. Until this January, the closest I had come to our military was trying to place flowers down the gun barrels of Army soldiers when I joined Abbie Hoffman’s attempt to levitate the Pentagon in 1967. I recall the soldiers, with their bare steel bayonets thrusting at us, were not amused. We also were not successful in our half-hearted attempt to mess with America’s war in Asia. Mostly I remember what would become my first taste of being teargassed, which unfortunately would not be the last time I (and my generation) was on the receiving end of an expression of our government’s displeasure with our attempts to voice our grievances about the war and racism.

What is interesting is how quickly I have become comfortable with the Marines at the battalion. Both the wounded Marines, as well as the senior staff NCOs, reveled in giving me endless amounts of crap about my hair. I learned to respond to their calls of “hippie” and insinuations about my seeming lack of “manliness” by addressing them as a bunch of “sissy little schoolgirls.” Beneath our snarky wisecracking to one another is something more than just a bunch of macho gallows humor. I have come to understand all this as a form of appreciation, of actual affection.

Soldiers, sailors, and Marines these days are quite comfortable with hugs. (Keep it brief.) Affectionate referrals as “brother” are another sign that you are being accepted as one of their own. There is, in fact, an immense amount of love and caring for the wounded and injured at the battalion. It’s why I’m there, it’s why the staff is there, and it’s why all Americans should be there!

I have learned that one is always a Marine, either retired, reserve, or active duty, that there is no such thing as a “former” Marine. Once a Marine, always a Marine!

Walking back into my family’s home after a week filled with the care and teaching of America’s wounded is the other end of my déjà vu moment. It is a comfortable place to return to: good food (yes, I’ve tasted MREs, yuck-puck), sleeping in my own bed, cuddling with my wife, Kathryn, taking my dog for a long walk on the beach, and generally being the real civilian bum that I am!

But I have learned a lot from America’s warriors. After all, any teacher, if he is really any good, learns in equal parts from his students. The Marines have taught me the true meaning of honor, of courage, of commitment, and I love them for it.

My photography students are in pain a great deal of the time, both physically and mentally. They don’t talk about it that much; they will simply tell you if they are having a good day or a bad day. PTS (post-traumatic stress) and TBI (traumatic brain injury) are a constant with a great many of these men and women. I have heard PTS described as a warrior’s shadow. Your shadow is always there, all the time; you can feel it following you throughout your daily life. The task our wounded bear is to learn to live with their “shadow.”

I hope that what I do while I’m with the Marines might ease their pain, just a little, or offer them hope, that it lets them know we civilians from the “the real world” care about their lives, their futures, as they move toward their own “civilian-hood” themselves, that it assures them that with a little effort, life will one day be somewhat more comfortable for them. And that America is not totally “at the mall.”

If any of this is understandable, if it has any meaning, then I will be happy to be living in two worlds.

Terence Ford is a professional photographer and an instructor in the fStop Warrior Project.