In Time of Drought, State Water in Serious Doubt

Central Coast Water Authority Issues Bombshell Warning

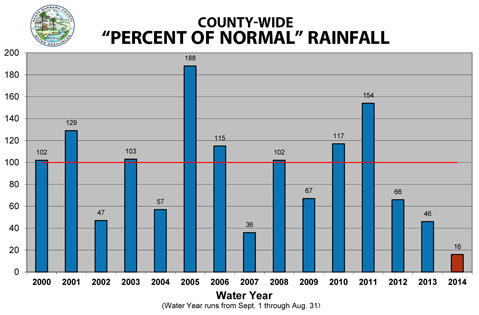

With much of the country recently seized by a freakish arctic vortex, Santa Barbara’s record-breaking temperatures and perpetual blue skies must seem nothing short of miraculous. But as the county enters its third consecutive dry year, the chief miracle its residents are praying for is rain.

Based on long-term weather forecasts, they’re not praying nearly hard enough.

The problem, obviously, is of statewide scope, and this Friday, California Governor Jerry Brown responded by officially dropping the D-bomb on all of California, declaring a drought emergency. Last year was the state’s driest in recorded weather history — 119 years — and this year’s snowpack in the Sierras is less than 20 percent of what it needs to be. Brown’s declaration calls on customers and water districts alike to cut back by 20 percent. It loosens the regulatory shackles on water agencies seeking to buy emergency supplies from other jurisdictions or water-rich rice farmers. And it relaxes environmental requirements that water be diverted for endangered fish species.

In similar fashion, the County of Santa Barbara declared a water emergency of its own the same day. But almost a week before, the City of Solvang beat both the governor and the board of supervisors to the punch — declaring a Stage 1 drought alert and calling for a 15 percent cutback in water use by its customers. Daytime irrigation has been outlawed, as has car washing and sidewalk hosing. Violators will be given two warnings and then socked with a $30 fine.

Solvang’s problems stem from the fact it relies almost exclusively on supplies delivered by the state-water system. This year, the Department of Water Resources (DWR) announced it could deliver only 5 percent of the state water the system’s member agencies are contractually allocated. That means Solvang — which relies almost entirely on state water to deliver 1,500 acre-feet a year to its customers — would get only 75 acre-feet.

In the 60-year history of the state-water system, deliveries have been this low only once before.

But late Friday afternoon, the problems of Solvang — and every water agency reliant upon state water — got a lot worse. In Santa Barbara County, that’s every community with the sole exception of Lompoc, whose voters rejected state water in 1991.

Ray Stokes, head of the Central Coast Water Authority (CCWA) — the joint powers agency responsible for importing state water into Santa Barbara County — quietly dropped a bombshell of his own, sending out a memo to county water managers that there may not be a single drop of new state water available this coming year.

Zero deliveries.

Not once has that happened before.

Citing the record-low rainfall and negligible snowpack, Stokes wrote, “There is a very real possibility that DWR may decrease the 2014 delivery allocation from the current 5 percent amount to zero percent.” And because of possible salt-water intrusion in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta — the pinch point through which all northern California waters must flow on their way south — Stokes said the delta may now be off-limits as a transfer point for potential water deals from north to south. That’s huge.

The only “good” news in Stokes’s bombshell is that the Department of Water Resources has about 800,000 acre-feet of water in storage reservoirs throughout the state. Of that, 14,000 acre-feet is carryover water “owned” by CCWA in the San Luis Reservoir. That’s water bought and paid for in previous years and put in storage rather than down the drain. Because the San Luis Reservoir is located south of the delta pinch point, those supplies should be safely available for Santa Barbara consumers. But Stokes isn’t taking any chances. “Essentially DWR stated we are in uncharted territory,” Stokes wrote. “I don’t want to sound overly alarming, but it would be very prudent for each CCWA project participant to carefully consider accelerating the requested delivery of water currently available.”

In other words, run, don’t walk.

At maximum pumping rates, all that water could be safely parked in Lake Cachuma sometime this June. Of the 14,000 acre-feet, 7,600 acre-feet would be set aside for South Coast agencies, and the rest would be allocated to North County consumers, the City of Santa Maria and Vandenberg Air Force Base being the largest. With this supply, Stokes estimates CCWA would have the capacity to deliver to 35 percent the agencies’ contractual allocations in the next year.

But would it be wiser to cut back now just in case?

Thirsty Customers, Crops, and Cows

Droughts, like fires, floods, and earthquakes, are integral to Santa Barbara’s ambient disaster-scape. They are inevitable, somewhat predictable, but — strangely — always a fresh revelation in how violent they can be. Superficially, droughts mean brown lawns, yellow toilets, short showers, and withered plants. They mean smaller fruit, dead trees, and wild animals encroaching into the urban zone and domesticated critters mysteriously disappearing. One water district manager described a drought as a slow-motion earthquake. Those most obviously shaken are those living immediately off the land. And along the way, droughts provide us all a very harsh lesson in humility.

In Montecito, home to some of the most lavishly landscaped estates ever imagined, the Montecito Water District board went beyond mere drought declaration, announcing it was facing a bona fide, right-here, right-now water shortage. If customers don’t cut back consumption by 25 percent, the district announced it could actually go dry sometime this fall. But in a place where some customers spend up to $8,000 a month on water, high prices and higher fines have little impact on water use. If cuts aren’t forthcoming, district manager Tom Mosby said he’s ready to attach flow restrictors to the water pipes of noncooperative customers.

Not all water districts on the South Coast are similarly afflicted. Carpinteria, for example, is endowed with a bountiful groundwater basin, unlike Montecito. Thanks to a decision made 23 years ago, Carpinteria signed up for far more state water than it ever needed or could hope to afford. Still, in the current pinch, state water — even now a hot-button issue in Carpinteria’s most recent water board election — has come in very handy. Despite such seemingly solid supplies, water boardmember Matt Roberts said he’s scanning the skies for storm clouds. “There’s not even a threat of rain,” he lamented.

Calling the current drought “epic” and “Dust Bowl dry,” Roberts — a longtime avocado rancher — is facing tough decisions about the fate of his trees. Without the customary winter rains, he’s been forced to irrigate his crops with water from the district on which he serves. That costs more but isn’t as good. “Rain is much more efficient, complete, and nourishing,” Roberts said. “It’s much higher quality.” With the drought, Roberts said his avocados will be significantly smaller. Smaller fruits also draw lower prices per weight, meaning he could lose money. “If this keeps up, I’ll be subsidizing my operation this year,” he lamented.

For the cattle ranchers, it’s tougher yet. Jim Poett, a longtime rancher from the Lompoc area, said he’s been forced to sell off his calves early for the past two years. “It’s very ugly,” he said. “Not locusts and that stuff, but very ugly.” Without the rains, fields that would normally be winter green are now fall brown. He and other ranchers have been forced to buy hay to feed their livestock, and the price of hay has been going nowhere but up. “If it’s still brown in March, then everything is gone,” Poett stated. “There won’t be any cattle. Some guys might keep a few head, but everything will be sold. This is it. Kaput. But we’re not there yet. It could still rain.” (Poett is the husband of Santa Barbara Independent editor in chief and co-owner Marianne Partridge.)

Water managers with the Goleta Water District say their customers have spent millions securing a diverse supply and drastically reduced per capita consumption to half the City of Santa Barbara’s and one-quarter of Montecito’s. Because of this, said district manager John McGinnis, Goleta should be able to squeak through the next two years without having to declare a drought of any kind. And though Santa Barbara water managers are confident they can make normal deliveries throughout the coming year, they announced they’d declare a Stage 1 drought in March. That’s mostly a gesture designed to promote greater public awareness and voluntary reductions. But still, it’s a year sooner than city drought-response plans are calibrated. In 2011, city water managers synchronized their alarm clocks to the South Coast’s six-year water cycle. Typically, Stage 1 alerts are called for only after three dry years. In this case, the declaration will come after just two.

Cachuma in Peril?

Even so, that’s not soon enough for Councilmember Bendy White, who served as chair of the city’s Water Commission during the crushing drought of 1986-1991. That’s when Santa Barbarans famously painted their lawns green and “water cops” were dispatched by City Hall to crack down on violators. Back then, City Hall entertained all kinds of crackpot schemes, like transporting water from Alaska via tanker or hauling icebergs down to Santa Barbara.

For White, lack of rainfall is only part of the problem. The scorching heat is another, baking the ground hard and dry, the backcountry vegetation into crispy kindling. If Santa Barbara gets no rain this month, it will be only the fourth time in recorded history that’s ever happened. “It’s scary-ass dry,” exclaimed White, who suggested that Santa Barbara’s natural cycle of floods and droughts might be accelerating. “I’m having the hair-on-the-back-of-my-neck sense that something’s not right,” he said.

Lake Cachuma, he noted, has plunged faster in this drought than it did in the same time 23 years ago. In response to unseasonably hot weather — and rains less than 20 percent of normal — dam operators are pumping water out of the lake as fast as they typically do in August, not January, while customers scramble to keep their outdoor plants alive. Lake Cachuma — by far the biggest source of water for Goleta, Carpinteria, Montecito, and Santa Barbara — has just dipped below 40 percent of its capacity this week.

If it dips below 30 percent — as it will by September, should present trends continue — Lake Cachuma’s water level will fall below two of the five portals into which the water is pumped on its way to South Coast customers. In that case, dam operators will find themselves forced to pump the water from a barge on the lake into the portals. The question is at what maximum capacity to calibrate the pumps. Currently, dam operators are looking at a pumping capacity of 44 million gallons a day. What makes that number striking is that the last time this happened — 1990 — the pumps had a capacity of about 17 million gallons a day. Although Randall Ward of the Cachuma Operations and Maintenance Board had no explanation for this leap, he acknowledged it was dramatic. “That’s not a jump,” he said. “It’s a crescendo.”’

Lake Cachuma currently provides 27,500 acre-feet of water a year to its member agencies. White expressed concern at a recent city council meeting that this amount could be largely reduced for several reasons. At some point, it appears likely that Cachuma operators could be ordered to divert a significant flow downstream to help maintain viable habitat for the federally endangered steelhead trout that once claimed the Santa Ynez River and its tributaries in prodigious numbers. Rebecca Bjork, Santa Barbara’s new public works director and former water director, cautioned there’s no way to know how much water the city could lose as a result of the steelhead preservation efforts and that any final decision remains a long way off.

A more immediate threat may be an apparent shift in professional etiquette among the water managers of the member agencies. In droughts past, there was an understanding among managers that when the dam dipped below 100,000 acre-feet storage, they’d voluntarily reduce their draw by 20 percent. This practice helped stretch limited resources and bought time for agencies as they sought to ratchet back consumption. But with Cachuma now well below the 100,000 acre-foot mark, this cutback has not occurred. “The level of perceived cooperation among member agencies is not as strong,” said Carpinteria’s Roberts. “There’s more of an every-man-for-himself attitude,” he said. In this case, the Goleta district balked. When Goleta declined to participate, the other agencies declined, as well.

According to McGinnis, Lake Cachuma provides his customers the cheapest glass of water they can buy. “If you have two glasses of water side by side, and you’re thirsty, you’re going to drink the cheaper one first,” he explained. “After that, if you’re still thirsty, you’d pay the extra money.” McGinnis added that the Goleta district will pump about 3,000 acre-feet of state water — much more expensive — into Lake Cachuma this year, and that contribution will provide the same net effect as if the district had observed the voluntary cutback tradition. Carpinteria’s Roberts noted, “Whenever water becomes scarce, there’ll be more arguments.”

Fluid Solutions

What saved Southern California from the last major drought was the Miracle March rain of 1991. Rarely has so massively messy an inundation been the cause of such mass jubilation. But between 1986 and 1991, South Coast water agencies and residents made major changes. Low-flow toilets and showerheads became ubiquitous, and drip irrigation more broadly embraced. Local governments invested in a new reclaimed-water-distribution system so treated sewage water, rather than drinking water, could be used to irrigate soccer fields and parks. Santa Barbara city residents cut their consumption in half, successfully spurred on by new punitive water prices. Prices stayed the same for the daily minimum needed for indoor use; after that, prices increased 16-fold. It worked.

Farmers embraced more efficient irrigation methods. Water districts adopted drought-management plans and hired conservation officers to show customers how to make every drop count. And local governments invested millions upon millions on new water supplies. In 1991, Santa Barbara County voters approved hooking into the state-water system for the first time, locking themselves — collectively — into annual payments of $50 million, whether they got any water or not. Likewise, South Coast voters approved the construction of a desalination plant — with a maximum capacity of 10,000 acre-feet a year. Upon completion, the desal plant stayed up and operating long enough to fill a few hundred plastic bottles with slightly salty-tasting water, but it has been offline ever since.

The desal plant currently exists more in popular imagination than in real life. Its components have long been mothballed; some were sold off, and many need to be replaced. In a best-case scenario, it would take two years and $18 million to get that plant up and running. In a worst-case world, the coastal commission would object that the plant relies on antiquated technology that inflicts undue harm to the marine environment and would require something other than what City Hall owns.

In this drought, the deus ex machina that will be invoked as the long-term fix to our chronic water woes is Governor Brown’s much-debated Twin Tunnels project. Brown has proposed building two massive pipes underneath the delta that would carry Northern California’s water safely — and with little environmental detriment — to southern customers. Proponents contend the Twin Tunnels will enable the state-water project to avoid the environmental pitfall of sending water through the delta, home of the famously endangered delta smelt, and thus increase the reliable delivery of an additional 800,000 acre-feet a year. The price tag for this project — depending upon the source — ranges from $25 billion to $60 billion. There’s no shortage of opponents lined up to fight this project tooth and nail, claiming the costs have been grossly minimized while the benefits have been vastly exaggerated. The current crisis will be seized upon by proponents, but under even the most accelerated timetable, there’s no possibility such a colossal project could be built in time to provide relief now.

Water Willies

The good news is that Goleta, Santa Barbara, and Carpinteria have solid groundwater supplies, though Carpinteria’s pumping infrastructure needs serious work. Solvang and Montecito have shallow aquifers with limited storage. In the past, well-heeled Montecitans, put off by past conservation campaigns or district interference, have drilled their own wells. According to Montecito district director Mosby, at least two dozen wells have failed in recent months. Others are encroaching on groundwater supplies upon which the district depends. Thanks to the importation of state water years ago, the Montecito district issued about 500 new meters to customers it otherwise could not serve. But for Montecito and Solvang to make it, they’ll need other water agencies — less reliant upon state water — to sell some of theirs. In a less cooperative landscape, that may prove easier said than done.

Santa Barbara’s reclaimed-water system, it turns out, has barely functioned for the past seven years. It’s now being taken offline for major repairs. When that work is completed two years hence, it will replace 1,300 acre-feet of potable water that could more directly meet human needs. In the meantime, that extra demand places additional drain on limited supplies.

When Santa Barbara’s first dam — Gibraltar Dam — was built in 1920, it was billed as the ultimate solution to the region’s water-supply challenges, capable of delivering about 3,000 acre-feet a year. (The city’s total demand is 14,000 acre-feet. ) Today, Gibraltar — located a few miles upstream from Lake Cachuma — is all but bone dry. “This is the first time in my life Gibraltar has been this dry,” said Russell Ruiz, a longtime water warrior and member of the city’s water commission. The dam has been rendered effectively inoperable by the vast buildup of silt caused by years of operation and severely exacerbated by deposits of ash and soil erosion caused by the recent Zaca Fire. At a recent City Council meeting, Santa Barbara Mayor Helene Schneider asked the cost of dredging Gibraltar. Sometime later, her colleague Councilmember White calculated it would take 1.6 million truckloads to haul.

For the time being, city public works chief Bjork is maintaining a posture of vigilant confidence, even with the recent revelations about state-water deliveries. “Am I nervous?” she asked. “As a water manager, I have to be nervous. But we still have a diverse supply, our groundwater’s in good shape, and we’re still on track to make normal deliveries this year.”

In the meantime, Councilmember White hasn’t shaken that feeling that’s caused the hair on the back of his neck to stand at perpetual attention. He remains spooked. In the meantime, he intends to play the role of Cassandra, warning his fellow councilmembers on a weekly basis how dry things are. “The only rain to fall at all in the whole state of California for the month of January was just a smidgen in Eureka,” he said. “That’s it! And January is traditionally when we feast.”

White recognizes all his hyperventilation could be for naught. He sincerely hopes it is. Intoning what’s become the de facto universal prayer for those seeking to ward off drought, White noted, “It could always rain in February.”

State Water’s Double-Edged Sword

Critics of state water have long contended that the system won’t be able to deliver when it’s most needed, because droughts tend to be statewide in scope. Certainly this is a case in point. But supporters of the system — and Santa Barbara County’s decision to hook into the state-water project at an annual cost of $50 million — contend that even when the system can’t deliver water, the pipes and infrastructure will give the regions the capacity to buy water from other purveyors Santa Barbara would not otherwise have. And they point out that the South Coast would be in far worse shape right now if it hadn’t banked previous year’s allotments in nearby reservoirs. It’s a complicated picture.

Montecito, for example, would be in a deeper hole than it currently is were it not for its ability to import state water. Since voters approved the hookup, Montecito took on about 500 additional customers — and the additional demand they put on the system. That would not have happened were it not for state water. At the same time, without state water, the district would lack the tools needed to secure additional supplies. Carpinteria’s picture is complicated in a different way. For years, state water has placed an intense financial burden on the small district that opted for an allotment of 2,000 acre-feet at a cost of $3 million annually.

Because there’s no guaranteed quantity of water delivered under the state-water system, water districts say they’re really paying for the pipes. So if Carpinteria were to get 100 acre-feet this year — as it would under the 5 percent delivery scenario — it would be at a cost of $3 million. The pipes, however, have allowed the cash-strapped district, which once boasted the highest rates in the county, to sell water in previous years to other districts. And with the onset of the drought, the Carpinteria district — once eager to unload its state-water obligation — is less anxious to sell.