How Irish Immigrants Saved Santa Barbara

A Look at the Legacy of Brothers Nicholas and Richard Den

Frank Edward Joseph McGinity is perplexed. How is it, he wonders, there are no streets named after Nicholas Den anywhere on the South Coast? No boulevards, bridges, public buildings, parks, or even a dusty beach trail. Given that Nicholas Den — the Irish immigrant who landed in Santa Barbara in 1836 — saved the Santa Barbara Mission from being secularized, helped navigate Santa Barbara’s painful transition from Mexican control to American authority, amassed an unimaginable fortune during the Gold Rush, chased notorious bandit Jack Powers out of town, and acquired pretty much all the land from Goleta to Gaviota, so conspicuous an omission seems all but intentional.

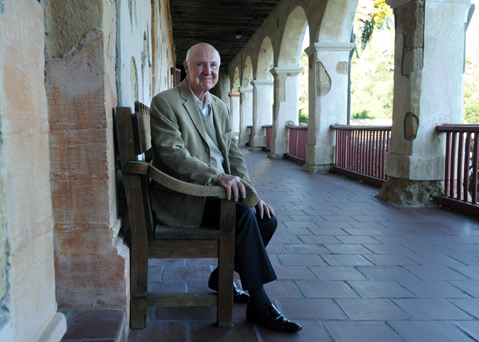

In recent years, McGinity — who heads the West Coast branch of the American Irish Historical Society — has set out to let the world know just who Nicholas Den was. As part of this mission, McGinity has been giving talks detailing Den’s exploits. “That’s what we do,” McGinity explained. “We’re Irish. We tell stories.”

That the World May Know

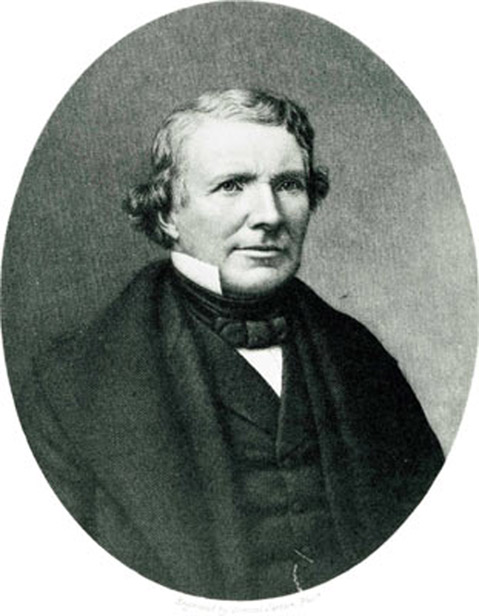

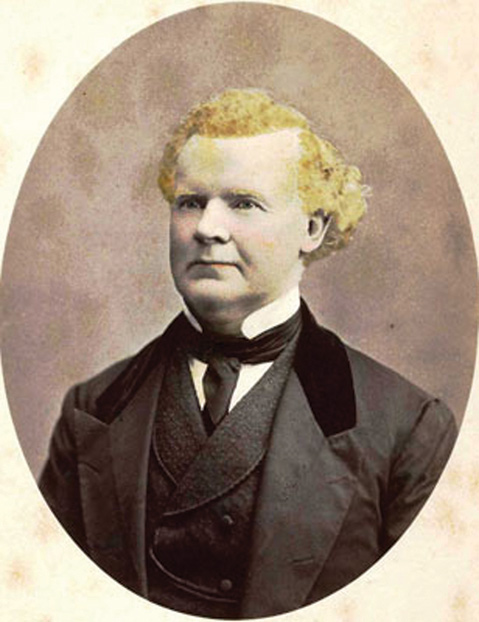

The American Irish Historical Society was established more than 100 years ago, “to set the record straight” McGinity explained, at a time when the Irish — Irish Catholics, especially — were widely considered third-class citizens. One of McGinity’s talks — held at Goleta’s Dos Pueblos Ranch, where Den once lived — spawned the production of a short documentary, Don Nicolas Den: Irish Pioneer to Santa Barbara, made by filmmakers Tina and Michael Love. (No relation to the Beach Boy of the same name.) The film, underwritten by the American Irish Historical Society, was a challenge to make, said Michael Love, because only one photo of Den exists. “There’s only so much you can do with one photo,” he laughed. The Loves’ film premiered last weekend at the San Luis Obispo Film Festival and will screen for the first time in Santa Barbara this Friday at Santa Barbara’s Carriage Museum. (Seating is limited, so reserve a space.) Also inspired by McGinity’s talk at Dos Pueblo Ranch was actor/writer/producer Shamus Murphy, who is now embarked upon a sprawling cinematic epic about Den’s life. In Murphy’s telling, Den not only embraces Chumash spirituality but also acts as protector to the surviving few still alive when Den arrives. Some area historians take exception to this interpretation, and Murphy acknowledges there’s been “pushback.” Currently Murphy has two scripts written and is trying to raise the $75 million he says the project will cost.

Today, McGinity — a quietly successful CPA — has offices along the tiled halls of Santa Barbara’s storied La Arcada Plaza. When McGinity moved there in 1998, he had no idea La Arcada was built on the site where Nicholas Den’s townhouse once stood. At that time, McGinity admits, he had no inkling who Nicholas Den was. One of the first places he read about him was in Royal Rancho, the popular history of the brothers Nicholas and Richard Den written in 1960 by Santa Barbara’s premier pop historian, Walker Tompkins. While scholarly historians have quibbled with some of Tompkins’s facts, Royal Rancho is acknowledged to be the most complete and accessible account of Den’s life.

The motto of the American Irish Historical Society, said McGinity, is “That the world may know.” Its mission — and McGinity’s — is to demonstrate that the reality of early Irish immigrants proved far more complex than the prevailing stereotypes of drunken, illiterate brawlers. As the fourth generation son of Irish immigrants who settled in “an Irish ghetto” in Brooklyn, McGinity acknowledges there was no shortage of discrimination. Even today, he bristles at the unconscious slights embedded in expressions such as “the luck of the Irish.” Such a phrase, McGinity noted, could only have been coined by the English. “It’s their way of saying that the Irish couldn’t do it on their own,” he said, “that they needed luck.”

But then there’s Nicholas Den.

Doctor Den Comes to Town

When Den, a stocky 22-year-old with bright blue eyes and blond hair, arrived in Santa Barbara, he showed up only slightly ahead of what would become the largest mass migration in human history. By the time the great Irish potato pestilence was done, a nation of eight million saw 1.2 million of its citizens killed by starvation and another million flee to faraway lands. Den’s personal exodus was not so tragically induced. He’d been studying medicine at Dublin’s Trinity College — until his family’s financial bubble burst. When a cousin in Nova Scotia offered Den a job, he jumped at the chance. But things did not work out. As Tompkins recounts, when the cousin ordered Den to polish his boots, Den began beating him until he fell “like a pole-axed ox.”

From Newfoundland, Den hopped a boat to Boston and, after a few months there, another to California. During a quick stop in Monterey in 1836 — then the capital of Alta California — he was advised to go to Santa Barbara, where he might find work with Daniel Hill, a Yankee from Massachusetts who had found wealth and fame in California long before gold was discovered in the north. He had married into the Ortega family, one of the wealthiest in Alta California; learned Spanish; and was living the life of a Ranchero grande: everything that was most appealing to the young man from Ireland.

When Nicholas Den arrived in Santa Barbara, Hill quickly schooled him on the facts of life in Alta California. The whole country was owned — and to a lesser extent controlled — by Mexico. If Den wanted to acquire land, he had to become a naturalized Mexican. Den wasted little time going native. In 1841, he became a citizen. He applied for and received his first land grant in 1842, and a year later he began squatting on a vast coastal property, once home to the two most populous Chumash villages on the South Coast — hence the name Dos Pueblos. Eventually he married Hill’s 16-year-old, Spanish-speaking daughter Rosa, with whom he’d raise 10 children. But to truly complete his transformation into “Don Nicolas,” he needed livestock. With money borrowed from a Mission padre, Den was able to buy 500 head of cattle that he turned out onto Rancho Dos Pueblos. The picture was now complete: Den had become a Californio.

Land Grabs and Beef Brushes

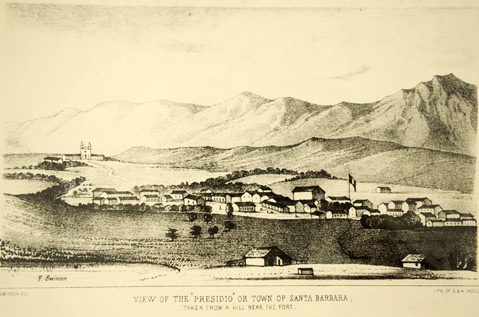

Santa Barbara, then a muddy town (or dusty, depending on the season) with only 900 inhabitants, was happy to allow him into its highest ranks. In a culture that honored hospitality, Den was renowned for his generosity. Every traveler along El Camino Real was welcomed at his table. His rancho fiestas were famous. And, perhaps more importantly, Den, though he never finished medical school, was the closest thing to a real doctor in the region. His bloodletting skills were widely appreciated.

This was a perfect time for ambitious men to be in Alta California. The Mexican government, which opposed church power and property, was in the process of “secularizing” the 21 Franciscan missions that ran the length of California’s 770-mile coast. In theory, secularization was supposed to liberate tribal peoples from the theocratic bondage of Franciscan missionaries. In reality, it proved to be one of the great land grabs in history. In 1842, Don Nicolas petitioned then-governor Pio Pico for legal ownership of the 15,000-acre Dos Pueblos Ranch. He got it. By then, his brother Richard had also arrived in California. He secured the 35,000-acre Rancho San Marcos. At one point, Tompkins reported, the Dens either owned or controlled 115,000 acres of Santa Barbara ranch land. Together, they and Daniel Hill would also acquire the Santa Barbara Mission itself and all attendant lands.

Politically and militarily, California in the 1840s was an absolute mess. At times, there were two governors, each vying for supremacy. It was rarely clear who was in charge or how much control they actually exerted. “Californios” bridled under Mexican authority that they found more oppressive than even the former Spanish government. Insurrections were frequent, though few bullets were exchanged.

The situation worsened when it became obvious the Unites States intended to take California and Texas as booty from the Mexican-American War. Den, then the elected alcalde, or mayor, of Santa Barbara in 1845, distinguished himself as an adroit politician, making nice with the Yankee invaders without openly bucking the Mexican authorities. His agenda, according to Hopkins, was to minimize loss of blood and life. His brother Richard, a skilled surgeon, served with the Mexican army, treating both Mexican and American wounded. (After hostilities ceased, Richard billed the United States for treating American servicemen captured by Mexico, but he was never paid.)

In the state’s gold frenzy of 1848, half the planet seemed to be racing to California. Nicholas Den, never asleep at the wheel, took advantage of what’s since been dubbed the “beef rush.” He was among the first rancheros to organize vast cattle drives — 1,000 head in the first one, 2,000 in the second — north to the mining camps. Cattle that sold for $2 in Santa Barbara fetched $50 there. Don Nicolas became exceedingly wealthy. In time, his Dos Pueblos rancho would boast 50 Chumash servants, its own orchestra, and a chapel. It even had what was completely unheard of — ice — shipped down from the Artic. Less charming was the fact that Rosa’s personal maid was her niece, the illegitimate daughter of a Chumash woman and her Hill brother.

Gangland Shoot Out

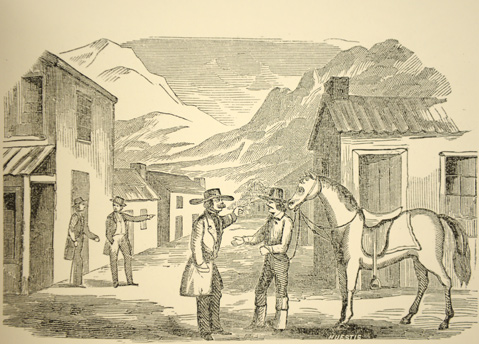

As the American flag was hoisted over California, Santa Barbara experienced an influx of new — and often disruptive — visitors and settlers. Before 1850, filmmaker Michael Love said, Santa Barbara had one saloon. After 1850, there were 50. With the vast new wealth came bandit gangs — often made up of former U.S. soldiers. In Santa Barbara, another Irishman, Jack Powers, led the most famous of these gangs. It was inevitable that there would be trouble between Powers and Den. According to legend, it came to a head when Powers, who is described as a skilled rider and charismatic killer, leased 1,000 acres — near present-day San Roque — from Den. He was supposed to have either rustled 1,000 cows from Den or refused to pay rent or both.

In any case, Den was determined to take action but insisted it be done legally. According to Tompkins, Den had been horrified when he witnessed a vigilante lynching in the gold camps. (Den later allowed a fugitive suspected of killing a crusading San Francisco publisher to hide out on his property for seven months because he was convinced vigilante justice prevailed up north.) Because of this, it appears Den always requested a legal writ served by the Santa Barbara sheriff before deploying any posse he organized, remarkable especially in this battle, considering the sheriff was often on Powers’s payroll.

The Den-Powers showdown between the bandit gang and Den’s posse and supporters played out over several years with public shoot-outs on State Street. Den’s ranch foreman was killed in an ambush. It got so dangerous that Den sold his Santa Barbara home to the Santa Barbara Mission and moved his family back to the secluded safety of Rancho Dos Pueblos. Eventually, Powers’s offenses grew so flagrant that not even public officials allegedly on his payroll could save him. He fled town, reportedly to Mexico.

A Spiritual Haven

Of the 21 missions in California, Santa Barbara’s is the only one to remain in continuous “divine service” since its inception in 1786. This is due in great part to the Den brothers allowing the church to remain open during the period that they owned the surrounding lands. This seemingly obscure factoid has had profound consequences for the role Mission Santa Barbara now plays as ground zero for historical research on the early European settlement of California and its impacts on native populations. As secularization closed other missions, its libraries, artifacts, archives, art, diaries, and baptismal, marriage, and death records were all sent to Santa Barbara, where they’ve been stored and shared with scholars ever since. Mission Santa Barbara boasts the complete works of Father Junípero Serra — now a gnat’s breath away from sainthood. It contains all the instructional books — how to plant, how to build dams, how to practice medicine — brought by the original priests who started the missions. The renowned anthropologist John Johnson of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History practically stammers when describing the raw historical record amassed at Santa Barbara’s Mission Archives. It’s so impressive that celebrities from Queen Elizabeth to Katy Perry seek private tours.

This would not be the case were it not for Nicholas and Richard Den.

By 1845, Governor Pico knew it was only a matter of time before the United States took over. Accordingly, he was in a hurry to sell or lease off all available lands. One theory holds Pico was intent in lining his own pockets; another was that he was raising the funds needed to repel the foreign invaders. Under either scenario, Father Narciso Duran, then in charge of the Santa Barbara Mission, was loath to see the Mission become fodder for Pio Pico’s going-out-of-business sale.

Duran knew the Dens and Daniel Hill. He provided the silver that allowed Den to purchase his first cattle herd. In July 1845, Duran wrote Pico that Den and Hill wanted to lease the Santa Barbara Mission for $1,200 over a nine-year period. He described them as “worthy and reliable.” In November 1845 — with Duran’s support — Pico approved the lease. Language in that lease specifically provided that the bishop and the friars would be allowed to remain. Two days later, Pico went even further, selling the Mission lands outright to Richard Den for $7,500. That sale would not be effective, however, until after the term of the lease had expired.

As Tompkins would write, these actions had the effect of “preserving it [the Mission] from desecration by infidels.” In more than 225 years, the Mission sanctuary light never went out. Less glowing in his assessment was Robert J. Moes, who wrote a brief monograph on the Dens in 1992. Moes would describe the two land deals struck just two days apart as being “redolent with the aroma of opportunism and intrigue.” The Dens, he suggested, “wanted land, chiefly for running cattle and they wanted title to this land.”

Whatever their motivation, the Dens allowed the Mission to remain open and operative as long as they held the Mission lands. Later — under American rule — the church would challenge the legality of the Den deals and prevail. The court ruled that Pio Pico had no legal authority to transfer either the Mission Santa Barbara or Rancho San Marcos. Subsequent courts would find that Pio Pico lacked the authority to lease or sell the land when he did so. In addition, Richard Den failed to take the legal steps necessary to claim title to the land when the lease with Nicholas Den and Brian Hill expired. As a result, the Mission reverted to Franciscan ownership. This led to two bitter, if unsuccessful, lawsuits filed against Don Nicolas by his brother Richard.

Nicholas Den died in 1862 at age 50 of pneumonia. In his will, Den decreed several hundred head of cattle each should go to various church functionaries. But the drought of 1863 — with temperatures so hot that birds fell dead from the sky — wiped out the Den herds. It probably didn’t help matters any that the executor of Den’s estate, Charles Huse, was acerbically and outspokenly scornful of all things Catholic. When the church sued to get the cattle or an equivalent, Huse sarcastically suggested God might have been responsible for the Dens’ inability to deliver the cattle owed. To make good on these obligations, Huse sold off vast chunks of Den’s empire to W.W. Hollister, then recently arrived to the county. That deal would be fraught with problems, as well. Huse, it turned out, had been an incompetent executor. He did not have the authority to make such sales. In fact, at the time of sale, a judge had warned Hollister of this. Hollister ignored the advice. It would take a bitter 14-year legal battle with the Den heirs to make him pay attention.

Ultimately, the Dens won. Hollister died, and the estate he built on Den’s land mysteriously burned to the ground. The fire was at Glen Annie, named after Hollister’s wife, who, legend has it, torched the mansion to prevent anyone else from using it after she was forced to leave. She always denied this. In any case, however, the Dens were eventually forced to sell off their vast landholdings.

In the meantime, Frank McGinity is determined to keep Nicholas Den’s name alive. “There’s a street up off of Barker Pass named Nicholas Lane,” he said, half in jest. “Maybe we could add Den’s name to that.” Mostly, McGinity is heartened that his efforts on behalf of Nicholas Den have generated any ripples. “It’s strange in Santa Barbara,” he reflected. “You start a thing, and it seems to go. I don’t know why. But it does.”