The My Lai Massacre’s Santa Barbara Connection

David Obst Helps Get Seymour Hersh’s Explosive Story to the People

Santa Barbara resident David Obst has an uncanny way of being in the right place at the right time. In 1969, Obst was managing a small anti-war news service called Dispatch News Service, a poor cousin of giant news services like the Associated Press or United Press International, in Washington, D.C., when his neighbor, freelance journalist Seymour Hersh, was trying without success to interest major American newspapers and magazines in an explosive story about the My Lai massacre, one of the worst atrocities committed by American soldiers against civilians during the Vietnam War.

My Lai is largely forgotten now, but it remains one of the darkest chapters in American history. During a search-and-destroy mission on a single afternoon in March 1968, American soldiers, without provocation and for no justifiable reason, murdered more than 500 women, children, babies, and old men. Many of the women were raped, their bodies mutilated. The South Vietnamese village of My Lai was set ablaze and burned to the ground. When Hersh’s exposé broke, thanks in part to Obst and Dispatch News Service, it contributed significantly to turning American public opinion against the war and earned Hersh a Pulitzer Prize in 1970.

Obst went on to a successful career as a literary agent, while Hersh broke many more important stories. On the publication of Hersh’s latest book, Reporter: A Memoir, Obst invited the Santa Barbara Independent to his Mission Canyon home to reminisce about how a couple of young guys with limited credentials and even less money pulled off one of the most remarkable coups in the history of American journalism. The twists, turns, blind luck, synchronicity, and sheer audacity — a trait Hersh and Obst shared in equal measure — are fantastic, the stuff of an Oliver Stone thriller.

Raised in Culver City, California, Obst was 23 years old in 1969 when he moved to the “belly of the beast,” as he called it, Washington, D.C. Obst had avoided being drafted by giving the Culver City draft board a choice: They could throw him in jail or let him do something useful with his life. The draft board gave Obst a deferment. That sort of pluck came naturally to the raconteur who could probably make a comfortable living selling space heaters in Phoenix in July. Prior to landing in Washington, Obst was bumming around Taiwan, learning Chinese and acting as an unofficial interpreter between Taiwanese bar girls and American GIs on R&R from Vietnam. That experience not only advanced Obst’s learning of Chinese, it also taught him an important lesson about the Vietnam War: Grown-ups lie. The stories GIs told Obst were completely at odds with what American military and government officials were telling the American people about the war. The government claimed the U.S. was winning; the soldiers said winning was out of the question.

When Hersh got onto the My Lai story via a tip that the U.S. Army was about to court-martial a soldier at Fort Benning, Georgia, for killing 75 civilians in South Vietnam, he was a freelance journalist working out of a rented office in the National Press Building in Washington, D.C. Lacking the aegis and umbrella of a major magazine or newspaper to open doors and pay expenses, all Hersh could rely on were his instincts, sources, nerve, and determination to expose the truth. Born on the South Side of Chicago to immigrant parents, Hersh was no stranger to hard work, long hours, and running over, around, or through obstacles. Through dogged persistence, Hersh finally obtained the name of the soldier being court-martialed at Fort Benning: William Calley, an officer, not an enlisted grunt. A source told Hersh that Calley was a madman, an aberration, but Hersh, a staunch opponent of the war, believed that Calley might be part of a larger story about an immoral, senseless war in which the killed and the killers were both victims.

Hersh’s My Lai story was too explosive for most major American outlets. Life, Look, Time, and Newsweek all passed, and Hersh was hesitant to approach the New York Times or Washington Post for fear his work would be altered or stolen outright. Having exhausted his mainstream options, he turned to Obst and tiny Dispatch News Service. “Don’t screw this up, David,” Obst recalled Hersh telling him. Obst had no idea how he would distribute the story, but that was a problem he would solve later, on the fly; first he had to sell it. Armed with a copy of Literary Market Place, a compendium of newspaper, magazine, and book publishers, Obst spent days cold-calling one newspaper after another. “It was like selling aluminum siding,” Obst said. When a paper such as the Hartford Courant agreed to look at the story, Obst took that to mean they would pay for and publish it and used that optimistic assumption to leverage other regional papers such as the Boston Globe, knowing that newspapers hated to be scooped by rivals. After pitching the story for several days, dozens of papers had agreed to publish it. When he told Hersh the good news, the future Pulitzer Prize winner was pleased but then asked Obst how he planned to get the story to all those papers simultaneously. There was no email or fax in those days. “I hadn’t thought of that,” Obst admitted with a laugh, “but I soon learned of a thing called Telex [a cable system for sending text], and even better, Telex collect.”

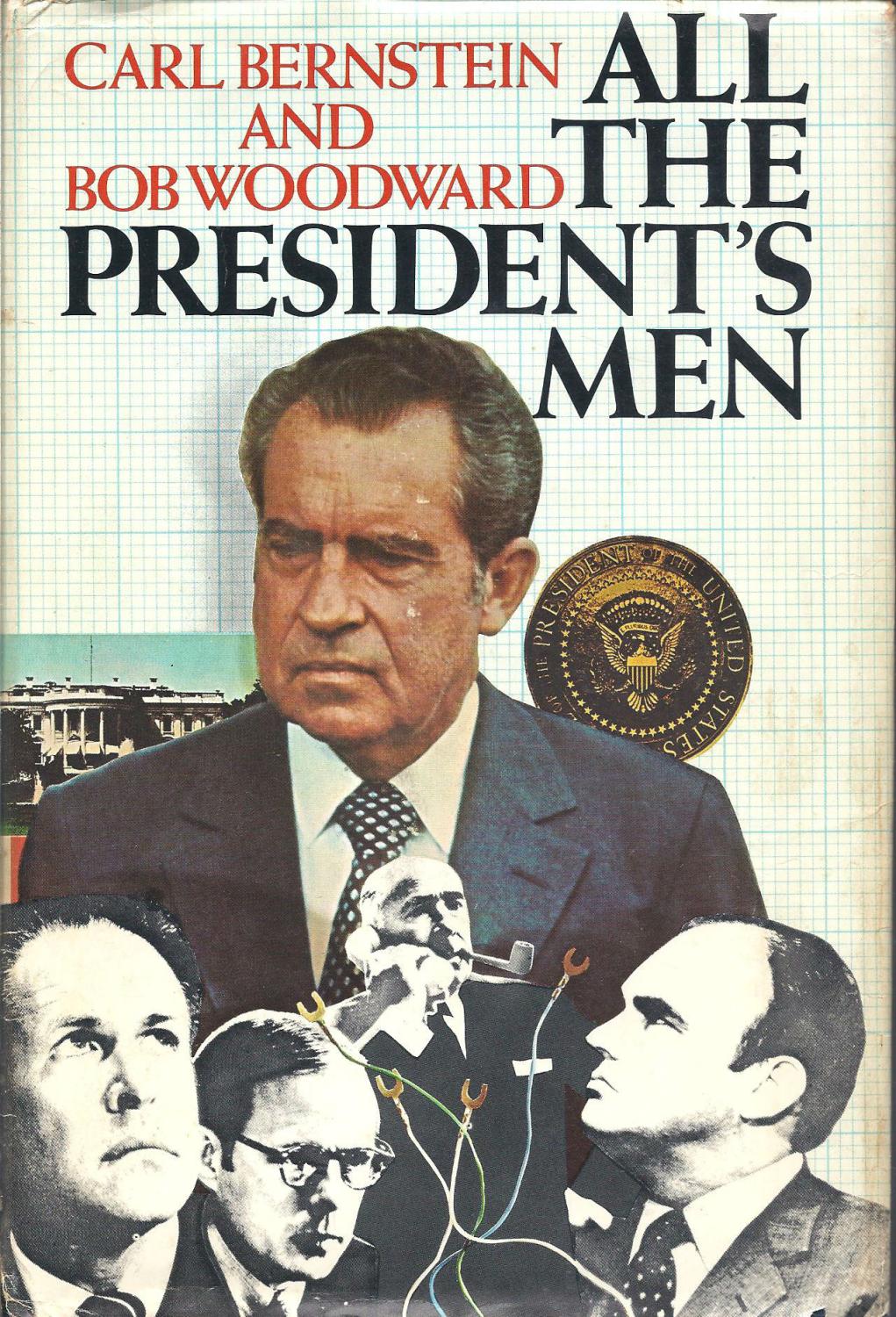

Obst went on to become the literary agent for a pair of Washington Post reporters — Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein — who, like Hersh, refused to let a story go until they had investigated every lead and confirmed every source. Woodward and Bernstein had a story to tell about the Watergate break-in and cover-up by the Nixon White House, and their book, All the President’s Men, contributed to the downfall and disgrace of President Richard Nixon. Looking back on his career with Dispatch News Service and as an agent, Obst, now in his early seventies, summed it up this way: “It was a great time to be alive, maybe the best time. We really believed we could change the world.”