UCSB Profs Discuss ‘Frankenstein’

Julie Carlson and Janis Caldwell Tell Why Shelley’s Novel is Still Relevant

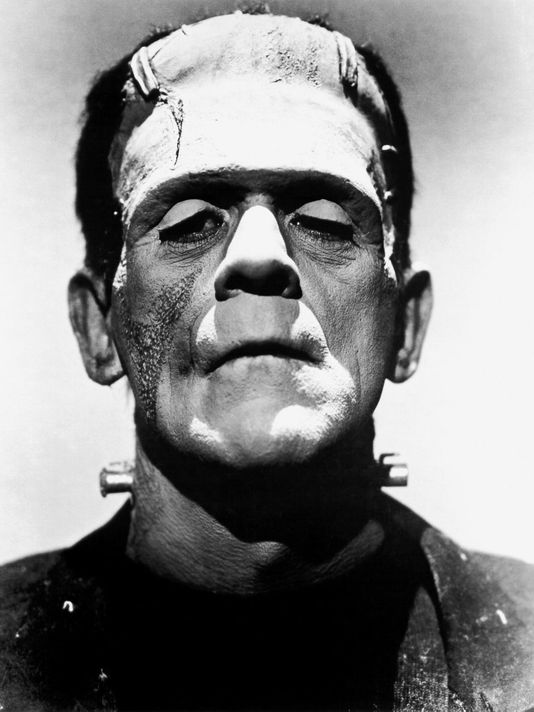

The city’s public library’s Santa Barbara Reads book this year is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. She wrote this tale in response to a contest among friends — which included Percy Shelley and Lord Byron — in which they were to devise the most terrible ghost story. The gothic horror was published as a book in 1818 and has become a classic thanks to Shelley’s complex imagining of Dr. Frankenstein and his creature.

On Tuesday, October 23, Santa Barbara Reads held a public keynote event at the Central Library with UCSB scholars Janis Caldwell, an associate professor of English, and Julie Carlson, professor of English, who discussed Shelley’s novel contributions to science fiction and literature.

The Indy caught up with them prior to their talk. The following is an edited version of the conversation.

Why is reading Frankenstein important today?

Carlson: Well for me, it stays so contemporary. It’s a text that in certain ways, is more true now than it even was then. What it’s envisioning is more realizable than it was fantasy. Now it’s close to reality. I mean more about technology — like the capacity to create life in a mode that isn’t heterosexual reproduction. But then also on the social political issues, it’s equally relevant.

Caldwell: One of the things that I see repeated in each of the nested tales of Frankenstein is this search for sympathy, and that’s something that doesn’t always come out when we talk about, “Oh you’ve created a monster!”, or when we’re worried about technology overwhelming our sense of ethics. So, the text itself is so much fuller and thought-provoking in a number of different forms.

What’s your favorite scene from the novel?

Caldwell: [Laughs] I think of the creature scaling the alpine crest. Just the vitality of his grandeur. He’s such a badass at that point in the story — he started to take his revenge, and the strength and the power — rather sounds like I’m reveling in acts of murder. But there’s this question of, “Why do so many readers feel sympathy for the monster?” There is this sense of righteous indignation. This guy doesn’t just dream the sublime…he is.

Carlson: [For me], it’s the creature’s account of reading, and how he says they were like and unlike me. He comes closer to an identification of literary characters than with humans. But then the rage is partly that the world bears no relation to those feelings for him. And I think that was such a powerful critique of the negative power of literature for people whose stories aren’t told.

What advice would you give to a first-time reader of Frankenstein?

Caldwell: I think one of the important first experiences of reading Frankenstein is figuring out whose side you’re on. What happens when you talk to other people about it? Where do you think the text leads you to put your sympathies?

Carlson: I don’t want people to think that the text is technophobic, that it’s simply like, this kind of messing the boundaries of life is horrible. Because we’re in a world where that question’s out the door. I think it would be too simple. I think the question of sympathy is more important.