Seeing Santa Barbara’s Past with New Eyes

Santa Barbara Public Library Digitizes More than 2,500 Historic Images

A treasure trove of rare photographs chronicling Santa Barbara’s earliest days has been liberated from a corner of the Central Library archive room and uploaded to a public website for all to admire and explore. “These photographs have been locked away in a file cabinet for over 60 years,” said Library Director Jessica Cadiente. “By digitizing them and making the images available online for free, we have not only preserved critical pieces of Santa Barbara history; we have made it available to anyone anywhere in the world.”

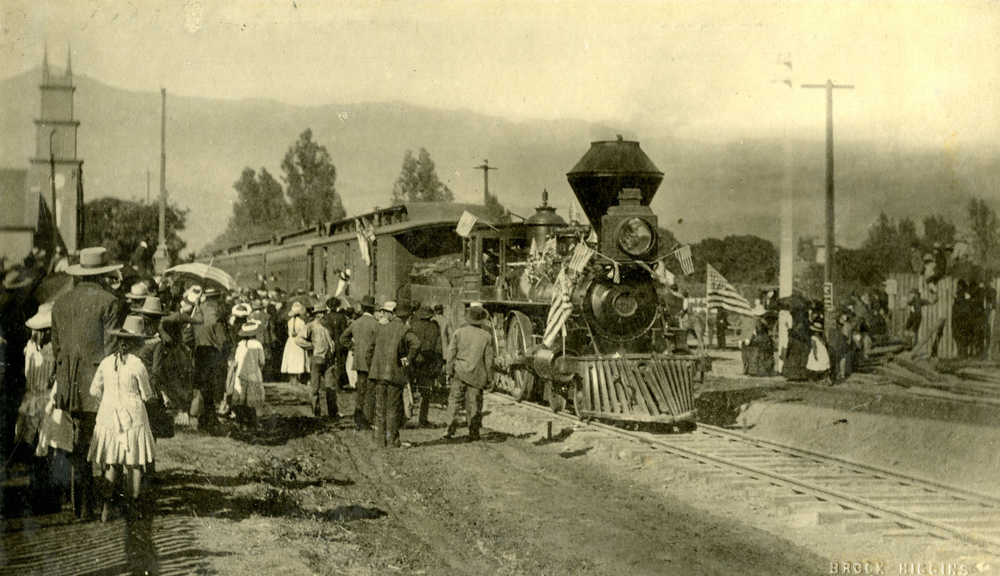

The collection of 2,500 or so images — dating all the way back to the first years of photography in the mid-1800s, when Ulysses S. Grant was president and State Street was a muddy thoroughfare of horses and carriages — depicts all corners of Santa Barbara life through the turn of the century. There are snapshots of Franciscan friars and De la Guerra descendants, the first Southern Pacific train and the old Potter Hotel, Fiesta celebrations and earthquake destruction.

The main building blocks of the series came from a man named Edson Ashley Smith. Born in 1887 along the waterfront near where Stearns Wharf now stands, Smith was the son of county undersheriff Rufus Dana Smith. After an early career as a bookkeeper for the United Electric Gas & Power Company, Edson Smith served as secretary of the Santa Barbara Club for 43 years. Throughout his lifetime, he amassed a collection of historic photographs, taking special pride in images of the city’s original adobes, construction of the downtown Fountain Saloon, and of a poll tax receipt that proved Richard Jenkins paid county treasurer R. Carrillo three dollars in 1857 for the right to vote.

Smith married and had a daughter, and upon his death in 1947, he willed his photography collection to Santa Barbara College (UCSB’s precursor), which later gave it to the library. Little else is known about the man, though his News-Press obituary states, “Santa Barbara Club members invariably found him considerable, helpful, and friendly.”

For the next six decades, Smith’s collection — along with hundreds of additional photos that had been donated to the library over the years — sat squirreled away, known only to staff and a handful of area historians. That is, until a fateful conversation took place in 2015 between Community Relations Librarian Jace Turner and art gallery owner Frank Goss. Turner expressed the library’s long-standing desire to digitize the images, to which Goss suggested he connect with John Woodward, a Santa Barbara attorney and historian with a vast photography collection of his own. The two met and brought on digital expert Lisa Lunsford to round out the team.

Woodward, a protégé of famed preservationist Pearl Chase, is paying for the project with a grant through the library foundation. Once it’s completed, he’ll support a new effort to catalog and preserve the library’s own archives, some of which recount the Faulkner Gallery’s opening in 1930. At that time, it was the only art gallery between Los Angeles and San Francisco and hosted the works of Picasso, Matisse, and Klee alongside performances by the London String Quartet. Reviews of the time slammed Picasso and called for more shows by Santa Barbara landscape painter Lockwood de Forest.

The process of sorting and scanning each individual photograph is tedious, admits Lunsford, but she enjoys the work. She’s carried out similar projects for the Mission Archive and the Maritime Museum and has developed a preternatural ability to identify buildings and faces, often correcting captions penciled on the back of the dusty, curling pieces of paper.

Last Thursday, she and Woodward sat hunched with magnifying glasses over a table spread with black and white pictures, gently debating but ultimately agreeing upon a few remaining details. “Getting the correct information is an ongoing process,” said Woodward. “It’s not 100 percent, but if we get 95 percent, I’m thrilled.” Crowd-sourced tips through the online portal will also help.

Among the collection’s many jewels are original works by Santa Barbara’s first resident photographers, E.J. Hayward and Henry Muzzall, who came from Indiana in the 1870s. They set up their studio in downtown’s tallest structure, the clock building, and captured panoramas of what was then an airy, pastoral community.

They also took images of the Mission with their stereo camera that produced two side-by-side photos from slightly different angles that would then be viewed with a special stereoscope. The technology didn’t yet exist to print photographs in magazines or books, so these images would have been looked at in awe in parlors across the country. Only about 30 percent of the collection’s photographers are known, their names stamped directly onto the negatives.

Now that the collection is publicly accessible, Turner hopes others will be inspired to let the library digitize their photos of historic merit. The hard copies probably won’t live there permanently, he said, noting the library isn’t set up for long-term, climate-controlled storage. But while Lunsford with her technical skill and Woodward with his unmatched knowledge are both available, it’s the perfect time to do the preservation work. They’re also on the lookout for 150 missing photos that were originally part of a 450-shot series. “If they’re around, they’re in somebody’s closet,” said Woodward.

Already, the website has generated attention, even overseas. The Salvatore Ferragamo Museum in Italy, dedicated to the legacy of the revered shoe designer, recently contacted the library because it had found photographs of Ferragamo’s first shoe store at 1033 State Street and wanted to use them for an upcoming exhibit. “We said of course! They’re all public, and they’re all free,” said Turner. “It was really neat.” Then just this week, Turner received a call from a family up in San Francisco. They’d also seen the site and wanted to donate prints of landscape designs by a Dutch relative hired by some of Montecito’s first landowners. “This is what it’s all about,” said Turner.

Beyond the collection’s wow factor, Turner went on, is its powerful reflection of Santa Barbara’s aesthetic heritage. It highlights what our region’s historians fight so hard to preserve, and it proves the city’s enduring appeal is no accident. “Part of the goal of this project is to reflect the reasons why Santa Barbara looks the way it looks,” Turner said. “There’s a reason why people want to live here, and I think it’s important for people of the younger generation to understand there’s a philosophy to that. It was very deliberate, very planned.”

To view the entire Edson Smith Collection, visit luna.blackgold.org. and follow the links. The Black Gold Cooperative manages the catalogs for libraries from Paso Robles to Santa Paula, and it features other rich photography series, including visual histories of Hispanic and native peoples along the Central Coast.