Day 5: They Got Game, Musically Speaking

David Crosby Doc and Aretha Franklin Live

Where were you during the Super Bowl? Large sectors of less-than football-obsessed people in town were drawn away from the Big Game by various offerings on day four of SBIFF. “They have Tom Brady,” quipped Michael Albright, the festival’s program director, at the Lobero yesterday, around the time of the Bowl’s second quarter. “We’ve got David Crosby and Aretha Franklin at the Lobero Theatre!”

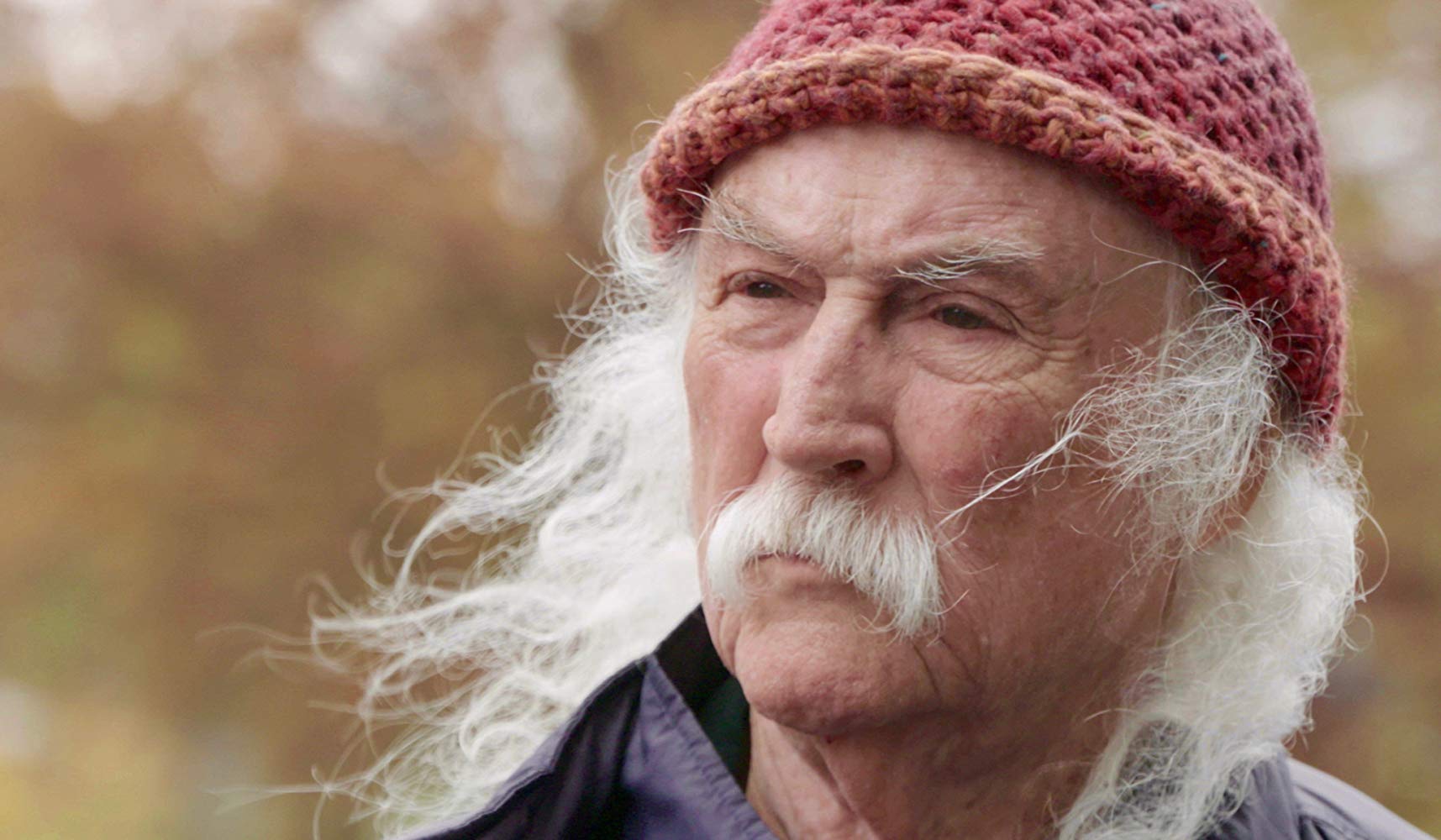

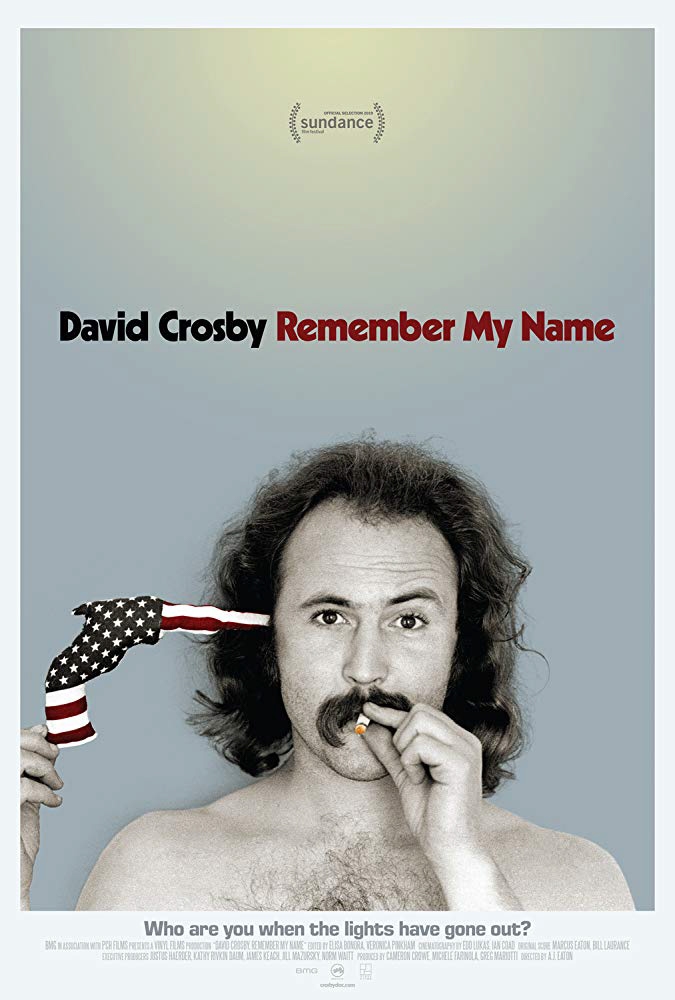

To back up a bit, Albright was referring to the double-header of music documentaries at the Lobero, as part of the “Cinesonic” sidebar of music-oriented docs he created when joining the festival eight years ago. Both of Sunday’s offerings — David Crosby: Remember My Name, and the revived live filming of Aretha Franklin’s 1972 gospel recording, Amazing Grace — were excellent, in their own special ways. “Croz,” now 76 and in the house for the screening, spoke volumes in his film while telling his tale and trying to make sense and amends for his famously boorish behavior over his long career; Aretha said nothing, yet spoke ecstatic volumes with her unparalleled soul queenly vocal powers as a singer.

Added site and city-based intrigue made for a natural byproduct of the surprisingly candid and self-revelatory Crosby doc. After all, he spent time growing up in the area (and as he repeatedly boasts “got kicked out of every school here”), has lived in the Santa Ynez Valley with his wife, Jan, and family for many years, and started his long association with the Lobero at age 17. Most recently, he brought his fine group of gifted musicians half his age, Lighthouse, to a concert at the Lobero last year, demonstrating Crosby’s remarkable late-breaking revival of creative energies.

Much of the Croz story is already well-known and covered with some added details in the film: his important early folk-rock work with the Byrds (before they canned him for bad behavior), carousing with the Laurel Canyon crowd, including Joni Mitchell and Graham Nash, launching the cash cow super-group Crosby, Stills and Nash (and later with Neil Young in the mix), which was “formed in 40 seconds,” according to Nash, and creating his 1971 poetic masterpiece of a solo album If I Could Only Remember My Name.

Later in the ’70s and ’80s came misadventures with hard drugs, hard times, and general mischief threatening to turn him into a rock casualty. He finally cooled and settled down, to a degree; only a few years ago he severely alienated old pals Nash and Young — perhaps for good — which, ironically, led him into his current burst of fresh writing and scheming with young musicians.

What is remarkable and magnetic about the film, which directed by A.J. Eaton and with no-hold’s barred interviews with director Cameron (Almost Famous) Crowe, is the seeming honesty at hand. The film does not follow the formula of the warm and fluffy “music star doc as marketing tool,” but is an affecting, genuine human portrait and of a local boy (and bad boy), still alive and artistically kicking with renewed fervor.

During the post-screening Q&A, Crosby affirmed that, “I’ve had a checkered history and an up and down life. We tried very hard to tell the truth. Cameron and A.J. weren’t interested in prettifying the story. I only had one job — to tell the truth.”

Amazing Grace needs no elaborate contextualizing, back story breakaways or checkered histories to convey its astonishing power. Here, in 1972, was a young but already famous and hit-making Aretha, wanting to return to her gospel roots and record an album live, in a church (the New Temple Baptist Church in Watts). The ambience in the church is palpable and riveting, with Rev. James Cleveland leading the show, before a crowd well populated with afros of the day. An obviously smitten young Mick Jagger is in the house, along with Aretha’s preacher/mentor father C.J. Franklin and influential older gospel singer Carla Ward.

Director Sidney Pollack was hired to film the event, but various obstacles have kept the film from being assembled into a screen-worthy form or from reaching our eyes, ears and soul. Thank God it has seen the light of day and reached eyes and ears: It’s a small miracle of a film. From the first song, “Holy Holy” through her mind- and soul-bending rubato version of “Amazing Grace,” to her father’s fave “I’m Climbin’ High Mountains,” and other gospel gems, the music is heated up in Aretha’s controlled furnace of a way with song.

Frankly, Amazing Grace, one of the true finds of this festival and all the more poignant with the Queen’s recent passing, approaches being a religious experience. Tom Brady would approve.

Melissa McCarthy Quote of the Day: Nobody, it seems, doesn’t like Melissa McCarthy, she of outlandish comic whiz bang, a hilarious parodist of Sean Spicer (the main reason we miss him is the chance to see her version on Saturday Night Live), and much more. That “much more” factor now includes wowing serious dramatic actress, as seen and appreciated by order of the Oscar nominators, in Can You Ever Forgive Me?

At last night’s tribute evening at the Arlington Theatre, she was intelligent and down-to-earth, and at the ready with the occasional left field persona. Her co-star Richard E. Grant gave her the Montecito Award and shared in a comedic lovefest with her at evening’s end. Speaking of her pratfalling, delightfully crazed and mold-busting roles, she admitted that “I fall in love with my characters, and you have to let them fall down. If you let them fall, you can’t watch them get up again.”

Films to See: Intriguing documentary filmmaker Dario Aguirre, an Ecuadorian-in-Hamburg now with official dual citizenship, returned to SBIFF this year, triggering memories of his sweet and inventive earlier film screened here, Caesar’s Grill, about his father’s restaurant in Ecuador. With his fascinating new film, Land of My Children, the ostensible storyline is simple: invited to apply for German citizenship after 15 years in Hamburg with his wife, he plunges into the maze-like bureaucratic process of getting beyond “being a foreigner.”

What may sound like slim material for feature length takes surprisingly deep turns, touching on the nature of geo-cultural roots, race, assimilation, and immigration issues. (In a post-screening Q&A, he addressed the subject of borders, calling them “an invention of the human being. I don’t know why. It’s not natural.”) Thanks to his history as a conceptual artist, Aguirre’s film also dazzles with visual energy, quirky twists, and cinema verité reflection, turning the sometimes self-indulgent genre of autobiographical docs into something deeper and more artful than it seems on paper.

[ Click here to view the complete coverage. ]