History Collides on San Andres Street

Dolores Huerta Deserves a Street Named for Her, but Don't Change San Andres Street

On August 15, 1973, Nagi Daifullah, a Yemeni migrant farmworker and a strike captain for the United Farm Workers union was killed at the age of 24. He was part of a picket line at the Smokehouse Café in Lamont, California, when Kern County sheriff’s deputies arrived to disperse the picketers. In the confrontation, Daifullah was clubbed by a deputy with his service flashlight/baton and then dragged with his head hitting the curb. He died of a broken neck and traumatic brain injuries.

It was the summer between my first and second years of law school. My first job in the law was as a volunteer for the United FarmWorkers’ legal staff. I made $5 per week. I worked for General Counsel Jerry Cohen and was assigned to investigate and track down witnesses to the Daifullah killing to testify at the coroner’s inquest. The question at the inquest was whether Diafullah had died (1) at the hands of another — and, if so, (a) by a criminal means or (b) by some other cause, or (2) as a result of an accident. We sought to prove it was 1a but hoped at least for 1b.

My first day on the job involved being a UFW legal monitor for a funeral march for Daifullah on August 17 on the streets of Lamont. Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta were among the 7,000 who attended Daifullah’s funeral.

The competing Teamsters Union had hired goons to threaten and commit physical assaults against UFW picketers. They gathered in groups on street corners along the parade route, rattling chains on the ground and pounding baseball bats into their fists. I took photos of the goons and kept crossroads clear of marchers when the streetlights turned red. Locals were known to gun their engines when farmworkers were crossing against the lights. Picking off a farmworker was high on their point system.

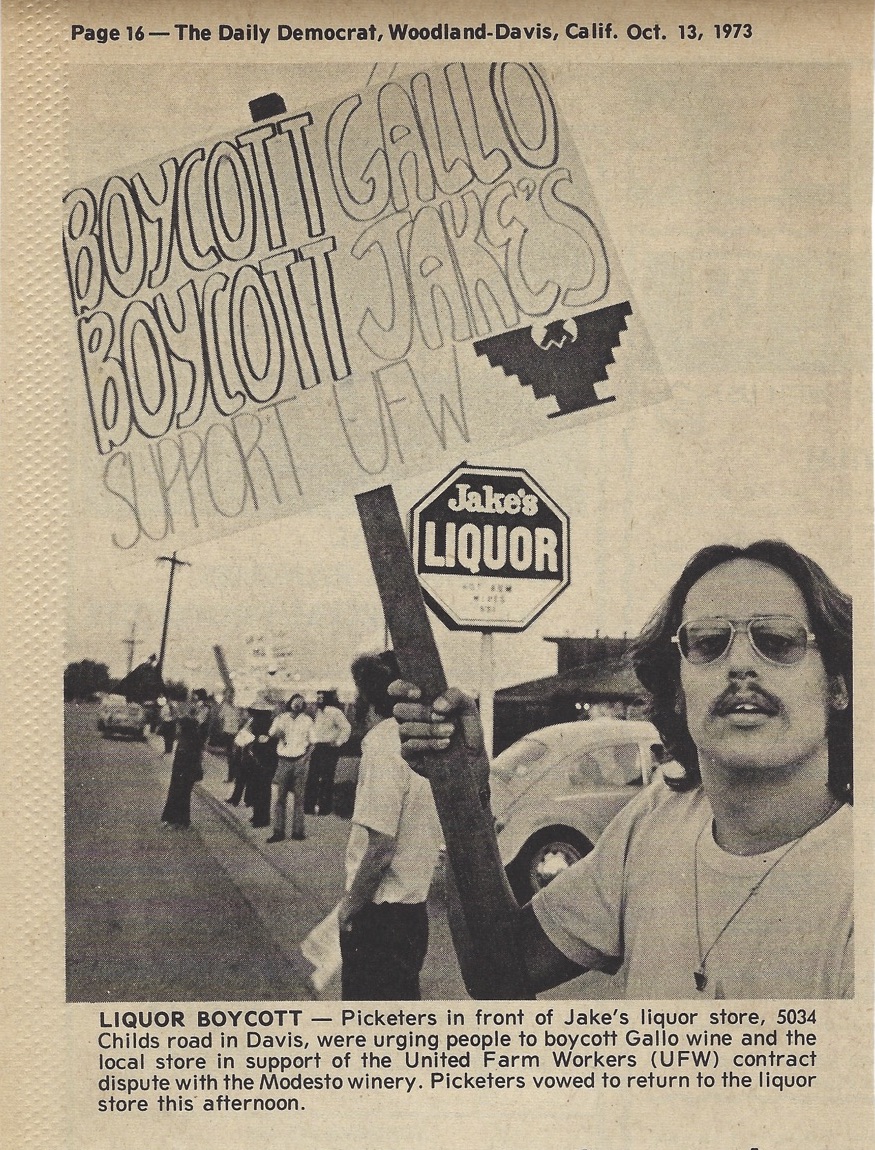

A UFW flag from that processional hangs in my office at home. When I returned to the UC Davis School of Law for my second year, I got on the picket line myself. A picture of my involvement hit the local newspaper. And yes, that’s my VW bug behind me.

César Chávez and Dolores Huerta hold honored places in the pantheon of souls who have deeply impacted my life in its developmental processes. That truth will never change.

But I see no reason to change the street name of San Andres Street to Calle Dolores Huerta. The question is not whether she is deserving of such an honor. She is deserving of that and much more. The issue is whether there is reason to change the name of a street named for another revered Californian in that process.

Name changes for streets in Santa Barbara are controlled by city ordinance. Municipal Code Section 22.48.030 states that, in regard to changing names of public facilities, including streets, “Existing names and names once established shall not be changed unless, after investigation and public hearing, the name is found to be inappropriate.”

The recent article by renowned Santa Barbara historian Neal Graffy entitled “The Battle of San Andres Street” sets forth the original historical reasons for naming the street after a venerable figure in Californio history. I need not repeat the laudable aspects of Pico’s life here. Graffy did it better than I could.

Another writer, Mr. Miguel Rodriguez, counters that “Andrés Pico Was No Saint” and presents a shallow argument for suggesting that the street name is “inappropriate” in an effort to implicate the ordinance. He points to Pico becoming a U.S. citizen and assertedly making “a fortune” on land “annexed from Mexican owners as spoils of war.” He also objects to the term “San” or “saint” being added to Andrés’s name in the street-naming process.

Andrés Pico did hold land throughout his life. He acquired several large tracts of land during the time of the U.S. war on Mexico from his brother, Pio Pico, who was then the governor of California. The lands were former Mission lands, which Governor Pico assertedly purchased from the Missions after leading the effort to secularize Mission lands. The United States government thereafter contested Andrés Pico’s title to the lands.

A quick review of federal and state reported cases shows no disputes with private parties over land rights between Andrés Pico and others. In each of the three United States Supreme Court decisions that bear his name as a party, the United States was his listed opponent. No private individual party was involved.

It is the case that Andrés Pico was a major player in the new state’s political system. He was elected to both the California State Assembly and the California State Senate after statehood. As a landowner with significant business holdings, he was often involved in court proceedings related to those endeavors. Andrés was serving as an elected official in the new state’s government while being forced by his new federal government to expend time, money, and emotional energy fighting court battles over title to his land.

The American legal system grew and developed after the war as a tool to dispossess many Californios and Mexicans of land holdings. The war was, after all, a pure land grab of Mexican territory by a neighboring country. Pico was, as were many of the Californio and Mexican landed class, dispossessed of lands and impoverished by the American takeover.

The legal system itself, the costs attendant to litigating one’s interests in an imposed foreign legal system, a new superimposed system of property taxation, and a variety of other mechanisms operated to wrest land rights from property owners under the Mexican system. Contemporaneously, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the war was ostensibly protecting those pre-existing rights.

Andres Pico may have been a person of substance economically, politically, and in terms of leadership in warfare at times in his life. If being “very rich” makes the naming of a street after that person “inappropriate,” we best break out the scissors for our street maps.

And no, Andres Pico was not a Saint in the ecclesiastical sense. But to call one a saint is to idiomatically adulate that person as a virtuous and honorable individual. So, our forebearers bestowed the appellation in a way that would be remembered by future generations.

History is malleable and is most often written by, and for, the conquerors, not the vanquished. But it is clear in our history that our forbearers determined that “San Andres Street” was an appropriate honor to bestow upon Andrés Pico in the 1850s in Santa Barbara. I have not yet heard the case that their honorific designation was “inappropriate” such that the street name of San Andres should be ripped from the annals of our collective history.

The fact that the 1851 Santa Barbara “ Committee to Name the Streets” named streets after both Spanish and Anglo surnamed individuals (San Andres and Gillespie) who fought on opposite sides of the Battle of San Pascual which General Pico arguably won (See Graffy article), is itself a testament and an honor to the civic history of Santa Barbara. They strove to bridge the cultural and ethnic gaps of the recent war in a very Father Virgilesque fashion. (Should Father Virgil Way be a consideration one day?)

Returning to Santa Barbara law related to street names, Section 22.48.020 of the Santa Barbara Municipal Code sets forth the “principles, policies and priorities” for the names of public facilities, including streets. Analytically, you only get to section 020 for a street with a pre-existing name if you have gotten past section 030.

If you assume that hurdle has been overcome, which is not the case here, 020 is implicated. So, let us assume that a hypothetical new street in Santa Barbara needs a name. Section 22.48.020 states that “as a general policy, names which commemorate the culture and history of Santa Barbara will be given first priority; those names commemorative of California history may be given second priority.” (Subsection “A”) Both Andrés Pico and Dolores Huerta qualify, at least as second priorities.

Also, “the name of an individual shall be considered only if such individual has made a particularly meritorious and outstanding contribution, over a period of several years, to the general public or interests of the City.” (Subsection “B”) In a wide-view sense, both are also candidates here.

And, “a preference shall be given to names of long-established local usage, names which are euphonious, and names which lend dignity to the facility being named.” (Subsection “C”) Again, either esteemed personage fits. Except that “name of long established local usage” for Andres Pico, goes back to the 1850s. Or even before.

Dolores Huerta is worthy of honorific recognition in our city, our state, and our country. But not by changing the name of San Andres Street. And yet, engaging in the discussion benefits us all. It requires us to re-examine and revive, or revise, our collective lens on history.

I return to the beginning. I know that Dolores Huerta had to be as upset as I was. The conclusion of the Daifullah Coroner’s Inquest was — a death caused by accident.

Frank Ochoa, an attorney, arbitrator, and mediator, and lecturer in the Chicana/o Studies Department at UCSB, served on the Santa Barbara County trial courts as a judge for 32 years.

You must be logged in to post a comment.