Taught or Not?

Literacy Lessons for Our Community

Read aloud the first word in the headline. How would you know how to spell it on first hearing? That word can be spelled three different ways! Lessons are taught, a tightrope is taut, and a small child is a tot. How do you know which one to write?

What about “they’re,” “their,” and “there”?

The conventions and relationships between spoken and written English are not a matter of intuition, and they are not automatic. They’re not a mystery, either. How we learn to read, decode, and make sense of language is well-understood by researchers around the world who have studied the “science of reading” for decades.

Widely respected expert Mark Seidenberg calls reading “one of the most complex human behaviors.” He defines this settled science as “a body of basic research in developmental psychology, educational psychology, cognitive science, and cognitive neuroscience.” (seidenbergreading.net/science-of-reading)

The instructional approach based on science is too often simply referred to as “phonics.” The method is far more complex and nuanced, and it includes mastery of phonemic awareness — or the ability to manipulate sounds in words — fluency, vocabulary-building, and comprehension. These skills blend together for reading proficiency. Importantly, this instructional approach is structured — direct, explicit, and sequential — and successful in teaching virtually every child to read, including those with learning differences like dyslexia.

Inexplicably, this research is widely ignored by the education establishment, both in teacher training and in classroom practices for reading instruction. Instead, the favored approach is based on a well-marketed theory known as “balanced literacy.” But balanced literacy is proven to successfully teach only half of students.

A child’s odds of learning to read ought to be better than a coin toss.

Unfortunately, that’s not the case, not here in Santa Barbara or across the nation. It’s estimated that 25 million American children are below proficient in reading. California reading proficiency is 49 percent; in Santa Barbara County, merely 46.5 percent of students meet the standard of reading proficiency.

For far too long, educators have wrongly blamed reading struggles on the assumption that floundering children have a bad work ethic, poor attitude, or low intellect. And parents have been routinely blamed for not caring, not reading to their kids, or for their socio-economic circumstances. In fact, children from all income levels and backgrounds experience reading deficits. Parents: Children do not outgrow reading difficulties. They must be effectively taught to read.

Somehow, the method of reading instruction has escaped scrutiny for too long. The time has come to focus our attention on the irrefutable fact that only half the children in our midst learn to read proficiently in our public schools. And balanced literacy is the culprit.

The proof isn’t hidden away in scientific journals. It’s widely known in popular media.

In a recent front-page report of the Sunday New York Times, one of the leading proponents of balanced literacy, Lucy Calkins, recanted her influential view on “balanced literacy” based on her new interest in scientific research. She is rethinking her widely embraced “Units of Study” program and reworking her K-2 curriculum as a result. (nytimes.com/2022/05/22/us/reading-teaching-curriculum-phonics.html)

Calkins’s 11th-hour recognition that her popular and lucrative reading business is deeply flawed is too little too late for a generation of schoolchildren. As adults, they now bear the consequences of the decisions made by an educational establishment that selected and funded the balanced literacy reading approach with little understanding of its long-term detrimental effects.

Education writer Emily Hanford systematically studied America’s literacy crisis in a series of groundbreaking reports for American Public Media. Her work has clarified what frustrated parents and advocates have been saying for years: Reading instruction isn’t working all across the country. And instituting the science of reading is the obvious solution. (apmreports.org/profile/emily-hanford)

In response to the bright light shined recently on low literacy, enlightened members of the education establishment are finally saying enough is enough. In nearly half the states, and in communities from New York City to Denver to Oakland, they have banned “balanced literacy” in favor of the science of reading to improve their reading instruction and outcomes for every student.

It’s what we need to do locally as well.

The Status Quo Has Got to Go

‘Wait to Fail’ Is a Failed Strategy: This common practice of waiting to see if students catch up on their own is fundamentally flawed. Children who struggle to read in primary grades are likely to continue to struggle the rest of their lives. Remediation is expensive, time-consuming, and rarely as effective as getting it right early on.

Intelligence: Reading struggles are not a reflection of cognitive ability.

The 3rd-Grade Wall: Children who do not master reading by 3rd grade are more likely to drop out of school, experience homelessness and mental health issues, and are even at risk of incarceration.

Balanced Literacy’s ‘Three-Cueing’ Approach: Guessing, skipping words, or searching for “contextual clues” from pictures are not effective “reading” strategies.

Closed Doors, Broken Dreams: Struggling readers are unable to meet the demands of higher education, even at community colleges where remedial courses are no longer offered.

Bleak Employment Opportunities: In today’s “information age,” poor readers are unlikely to find employment that pays a living wage, much less one that allows them to advance in life or fulfill their earning potential.

The balanced literacy theory sounds lovely: If you surround a child with rich literature, they will become joyful, lifelong readers. But it’s sort of like thinking if you place a child in a Ferrari, they will learn to drive. Or if you throw them into the deep end of the pool, they will learn to swim.

It’s time we abandon this sink-or-swim approach to reading instruction and let science lead the way.

Questions We Must Answer

• Where are children supposed to learn to read if not in public school?

• Children of parents who can afford specialized tutors may eventually overcome the instructional deficiencies inherent in balanced literacy. Those who do not have thousands of dollars to spend on remediation are stuck. Where’s the equity in that?

• What is the acceptable percentage of reading failure in children in our classrooms? In individuals in our community?

• What is the obligation of public schools to those now-adults who passed through but never learned to read proficiently?

Low literacy affects the health and welfare of the entire community. Our community must own the importance of early literacy proficiency. It’s imperative we set a literacy baseline that isn’t dependent on the turnstile of superintendents, administrators, and school board members who may or may not understand or want to follow the settled science.

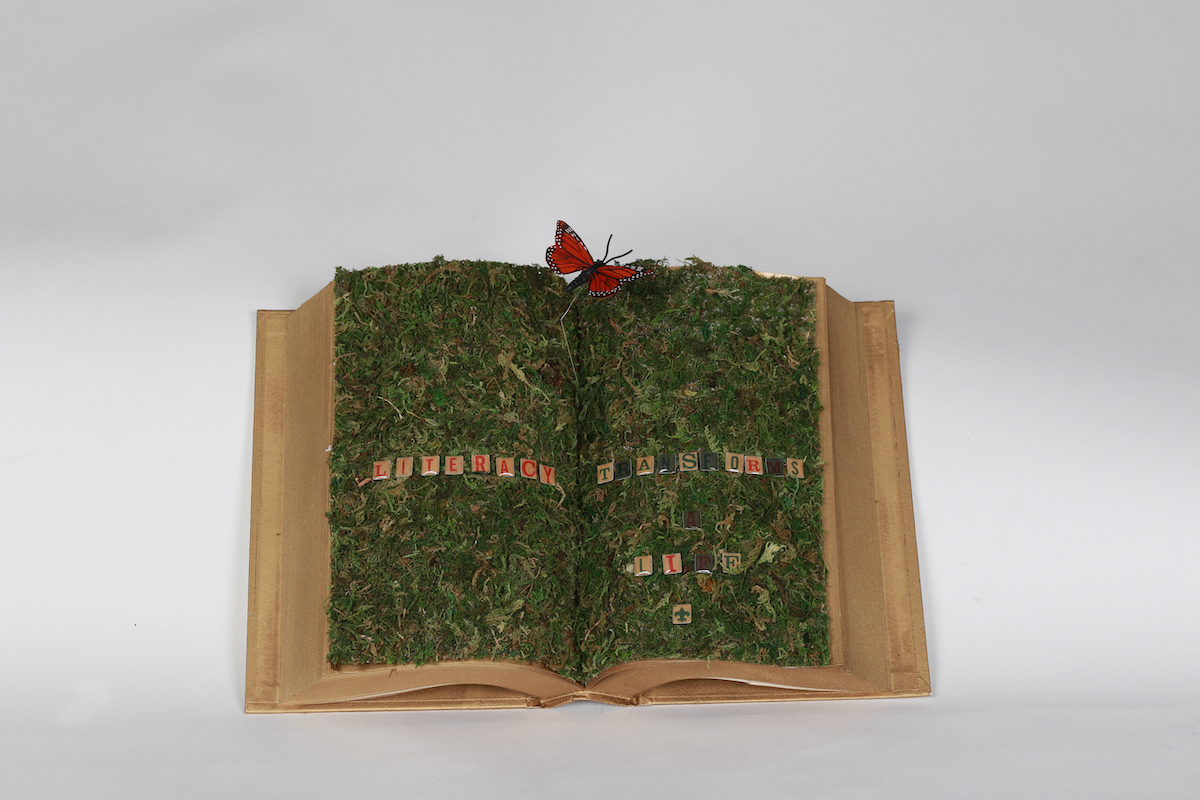

Literacy is a human right for a reason. Without it, children barely survive, and with it, they thrive.

It’s time to recognize that Literacy Is For Everyone. Not half. Everyone.

Cheri Rae is a member of the S.B. Unified School District Early Literacy Task Force, and Monie de Wit ran for SBUSD school board with a platform on literacy. They established a literacy resource center where they meet with families, educators and community leaders. They offer awareness, support, and a wide array of creative approaches to empower those who need assistance for struggling readers. Contact them at thedyslexiaproject@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.