Natural History’s Future

Retiring Museum Director Karl Hutterer Reflects on the Past 12 Years and Next 100

When he retires next month after more than 12 years at the helm of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, Karl Hutterer will enter the next phase of a remarkable life — one that began in the dirt as a young Austrian farmer, briefly turned toward the clouds as a Catholic priest, and then spent four globe-trotting decades as an archaeologist, professor, and administrator striving to bridge the intellectual, academic, and bureaucratic gaps between earthly realities and heavenly ideals.

But what may become his most enduring contribution — the leadership that’s behind an evolution and expansion of the museum’s historic Mission Canyon campus, which was first built in 1923 — remains in the very early stages of the public planning process, with even the most optimistic estimates putting groundbreaking no sooner than 2017. So while he’s done everything asked for by his board and much more, the 72-year-old will be leaving his post at the most critical turning point in the museum’s century-long history, and his departure is causing both worry and hope for fans of the museum, depending on what they think of the plan and the future.

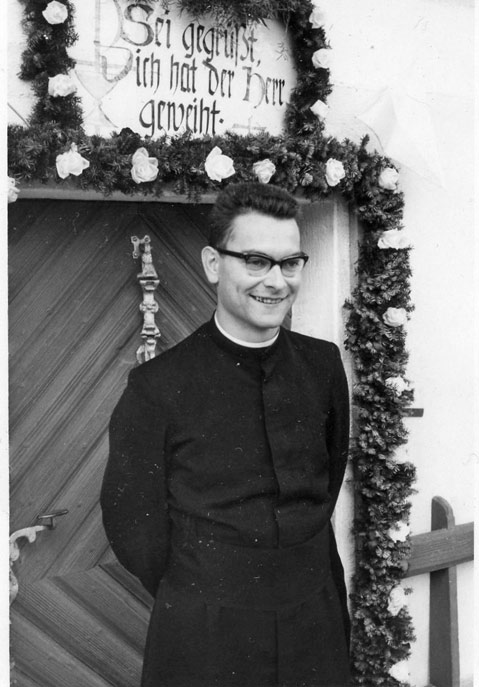

As for the past, Hutterer was born in 1940 on a farm in the Alps where his family has lived completely off the land for more than 400 years. “It was a Neolithic upbringing,” said Hutterer, whose family even made their own wool socks, which he recalled being “scratchy as hell.” At 18, he told his parents that he wanted to become a priest — his devout mother was thrilled, but his father just figured his son couldn’t handle manual labor.

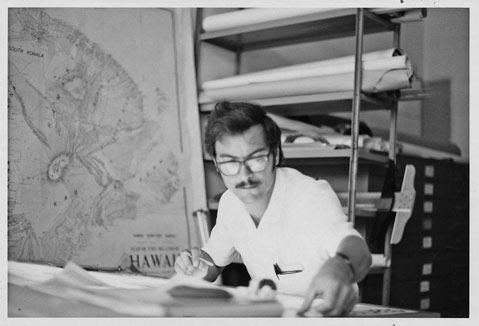

After seven years of study, he went to the Philippines as an ordained priest, but spent most of his time doing archaeology. Four years of that work, which included unearthing a settlement once visited by Magellan, eventually lured him away from the priesthood in 1969 and to a doctorate program at the University of Hawaii, where he studied Thai and Filipino prehistory, made $200 a month as a research assistant (“it was the richest I’d ever been in my life”), proposed to his would-be wife, Nancy, during the lion dance in Honululu’s Chinatown on Chinese New Year in 1972, and got his Ph.D. in 1973.

That same year, he got a job at Bryn Mawr, and a year later, the University of Michigan came knocking. As the number one school in the country for archaeology at the time, it was a “dream job,” but Hutterer felt doomed to fail. “Every one of my colleagues was amongst my idols, and I came with a third-rate education,” he explained. “I was convinced I would never last. Sooner or later they would discover I was a fraud.” But he excelled, was tenured early, and — at a dean’s request but against his own desire to remain in research and teaching — began his administrative career by taking over the then-failing Center for Southeast Asian Studies, which he saved from sudden death with creative collaborations. He then took a job as director of the natural history museum at the University of Washington, and endured his only notable failure, when plans to move the mildly attended museum to downtown Seattle (where more people would visit) were scuttled by “last minute cold feet.”

Meanwhile, the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History was looking for a new leader. After 22 years under the beloved Dennis Power and a brief stint by a replacement who found Powers’s shoes impossible to fill, the museum was being carried on the shoulders of two co-executive directors, Brian Rapp and David Anderson, who had put their legal careers on hold to keep the institution afloat. “They made the museum change-ready,” said Hutterer of his predecessors. “So when I came in, it was really an easy ride.”

Hutterer has made it look that way ever since, but as the face of the museum’s increasingly controversial expansion plan, he’s managing to poke the hornet’s nest on the way out. Critics include neighbors nearby and further up-canyon who fear the impacts that might come from increased usage, specifically related to traffic, noise, and wildfire safety, as well as others who simply love the museum as is and want to see its quaint nature preserved. Altogether, the concerned chorus seems to be gaining in volume, although how many individual people are doing the singing remains to be seen.

Come January 14, 2013, Hutterer passes that challenge onto Luke Swetland, who was named the museum’s new president and CEO last week. “He’s an outstanding museum professional with experience in leadership positions at several major museums in California and elsewhere,” said Hutterer of his replacement, who worked most recently at the Autry National Center of the American West in Los Angeles. “While he has not served at a natural history museum before, he has great expertise in the museum field more broadly and brings the vision necessary to lead the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History into its second century.”

This past September, in anticipation of his retirement, Hutterer invited me to lunch at the Santa Barbara Yacht Club, which offers honorary memberships for museum directors in town.

Did you get much direction from the museum’s board when you started?

The main thing the board had decided was that its number one priority was to rebuild the Sea Center. I, frankly, was a little aghast by this direction. I had done my due diligence about the museum and knew that the main facility in Mission Canyon desperately needed work. Most of the board didn’t realize how much the main facility needed. It’s such a charming, engaging place that you overlook what’s wrong with it. Interestingly enough, at one of my welcoming receptions, one guy, who has since become a very good friend, came over to me and said, “Karl, this place needs a lot of work. But there’s one thing you can’t change: Don’t touch the bird hall.”

Which you’ve since re-done.

Right. And he’s very happy with it. But it was an interesting indication of the way people feel about the museum: “It needs upgrading, but there are some things I like and you cannot change those.” You can go around the museum and every part has something like that.

What other major accomplishments do you see as being part of your legacy?

I have never looked at what I am doing here as a legacy at all. I’ve never done anything from that perspective. There is, first of all, very little if anything in physical terms. The Sea Center is one thing, but that was imposed on me, and I’m proud of the way we did it.

Most of my efforts over the years have been on the programmatic side. This is the essence of the museum. It’s building programs, not buildings. Our education programs have come a long, long way in the past decade or so. The Museum of Natural History has become the critical entry portal for science education for kids in our region. It truly functions that way.

Another thing I am really, really pleased about is that, over the past 10 years or so, we have reshaped the conversation in terms of what natural history is and what the natural history museum does. If I was to ask you to define natural history, I suspect you’d be struggling.

Well, it’s kind of everything.

It is absolutely. You hit it on the nail. But in the minds of most people, natural history deals with birds and mammals and geology and insects and, more than anything, it deals with nature as apart from humans. That is a very old fashioned, 19th century concept of nature and natural history.

Now we are in a stage of history where the natural world is in crisis. It is a crisis we produced as humans. There’s absolutely no escape from saying that. That means we have to think about the way we relate to nature and we have to understand that nature is everything. We humans are part of nature, we don’t just relate to nature. We are an intrinsic part of it. Everything in nature is systemically interconnected. Unless we get that message, we are missing the boat in a big way. It’s not a concern over polar bears who might be disappearing. It’s in our own interest as a human species.

You also got the museum to start looking at its own future.

In 2007, we got the board to really buckle down with long-term planning. We started with the question: What is a natural history museum in the 21st century? Who are we? What do we do? How do we make a difference?

You look not only at what Santa Barbara needs, but what do we have as resources to bring to that. You smash those two things together. In the museum currently, we have in the collections about 3.5 million objects. We have 14 full-time scientists. We have an education staff of about a dozen people. We have about 22,000 square feet of exhibits plus outdoors exhibits. So you think about how can you bring this to bear on the issues that currently are relevant in the community.

How do you balance being a cutting edge scientific facility with maintaining the quaint charm that people have come to appreciate?

Nothing we’re doing has to do with any desire to be bigger. It’s all focused on being better. Unfortunately, some of this requires us to be bigger. We have about 80,000 square feet of buildings right now. But besides being in terrible shape, they do not comply with virtually any code on the books. So one of the things our plan proposes is to demolish a significant number of old buildings, all those that are not historically designated, and build anew. In doing so, you have to add 40 to 50 percent of space just to comply to code. It’s called the grossing factor.

People think we can just remodel the building the way it is. We studied it very carefully. It would be very expensive, but we would also lose about 40 percent of existing space because of code.

Some say that there are enough scientific institutions in town, and why not leave that sort of work up to the people at UCSB? So why does the museum have to be a cutting edge institution?

Because natural history museums reach the people. Universities do not. They reach students. If you want to reach the people, we go right down to the very grass roots. We educate kids from age two onward. We have educational programs for every age group.

We do so much science, our curators. Just preserving that incredible font of natural heritage in our collections is huge. If you wiped them out, it would be an international loss of knowledge. This is our natural heritage. And we have a staff of 14 curators doing ongoing research, almost none of which is duplicated at a university. Every year, our curators define and describe dozens of new species. That’s pretty important.

Santa Barbara loves its red tile roofs and one complaint I’ve heard is that the new design uses a lot of glass and steel. Would it have been easier to just do the standard architecture everywhere?

First of all, that’s not actually true. We have to comply with the design standard of our historic district, and we are totally committed to do that. We have never said we wanted to do modern buildings, not once. What we did want to do originally is see to what degree we can reinterpret the Spanish Colonial Mission Revival architecture in a contemporary framework. It would be the same stylistic elements but maybe slightly less filigree.

One of the things I personally believe in very strongly is that the museum has to open up to this beautiful nature we have on our campus. We can’t get people in the museum and keep them away from it. There’s something wrong with that. So at one early meeting with the Historic Landmarks Committee, we did propose large windows, and they said no. We said, “Okay, we won’t do it.” We also had an issue with red tile roofs because, originally, our first request was for all flat roofs so we have have solar PV on it all, and they said, “No, you have to have red tile roofs.” So we are compromising on that.

Now, as far as design is concerned, it will be totally 100 percent mission-style architecture, even with all the filigree.

Is the plan progressing?

Yea. It just takes time. Ask anybody in Santa Barbara, right? It will be a protracted negotiation but I am fairly confident that, in the end, we will do what we want to do and what we feel we need to do.

Do you think that using a Santa Barbara-based architect would have been a better strategy? Your critics say you hired a former associate from Seattle.

We have a Santa Barbara architect on the team: Susette Naylor from Thompson-Naylor. She’s done some wonderful historic restoration projects in town, and she was chair of the HLC for a couple years, so we have first-rate representation.

The primary architect is from Seattle and someone I have known over the years. I argued for hiring him because I know how well he understands the programmatic and operational aspect of museums. That was extremely important for me. One approach is hiring an architect who designs a really great building and then figuring out how to fit the museum within it. That’s led to miserable situations. I said, “No, let’s do this the other way around. Let’s figure out what we need for our programs, and then let’s design a building around that.”

One of the members of the Historic Landmarks is an architect and he said, “You begin with the outside then you decide what you want and work your way in.” No, that’s not the way I want to do it.

What are your thoughts on the people who are critical of the new direction?

There are people who really don’t want to see the museum change. Whether deliberately or intuitively or unknowingly, they seize on a number of issues to fight that change. I understand completely, but I can’t start with that.

What is at stake with the museum is literally the long-term sustainability of a 100-year-old organization. I don’t just mean having enough money to run the thing. I mean an organization that truly makes a difference, that it relevant outside. If we can’t do the programs because of the ends we want to achieve, then we won’t succeed. We won’t get money in the door. But even if you could get the money in the door, if you are irrelevant, we shouldn’t be throwing money away from someone else. It literally is as stark as that.

That’s something that people who are so emotionally wedded to the lovely little quiet museum have a hard time understanding because that’s the way they grew up. They’re in their 80s, and that’s wonderful that they had such a wonderful life with this museum, but we are building for the next generation and the generation after that and after that. If you don’t understand that, I’m sorry, but I’m not gonna waste my time with you.

So the quirky little museum that’s managed to attract kids and adults and tourists is not a model that will last into the future?

I can guarantee you with 100 percent assurance that it will not last. In fact, it’s failing now. The only reason we are doing okay is because we have changed our programs to answer contemporary needs. But those programs are bloody hard to do with the current museum.

You first said that there wouldn’t be an increase in visitation, but now it appears there might be a rise, and that makes neighbors worried about traffic and wildfire safety.

Those are very legitimate concerns that we understand clearly. What we have said from the beginning is that we will not apply for a new CUP [conditional use permit] that is above our historic conditions. That remains true. What people didn’t realize is that historical attendance used to be a whole lot higher than it has been in recent years. In the late 1980s, we had some high attendance years, with 1989 being the highest at 196,000 people. That’s not just visitors, but community groups, staff, volunteers, etc. Last year it was about 150,000, and this year is closer to 160,000.

There is a lot of discussion in the Mission Canyon Association over what our historic attendance patterns have been and how they relate to traffic. Those are two very different sets of figures, very difficult to link, and people conflate them. They are not the same. The fact is that our attendance fluctuates from year to year. It has highs and lows. The problem is the CUP gives you a standard number.

There is actually a debate to what our current CUP is because we have several documents. One figure was given in 1988 as 150,000 and, in 1991, we were asked to submit a figure for adjustment, which was right after we had 196,000 in 1989. We have in our record no response to that, but the Planning Commission acknowledged getting that data. We assumed our CUP was adjusted upward. It was never adjusted to 196,000, we know that, because that would have been an allowable excess over the standard figure, which is usually about 10 percent.

What visitation numbers do you expect?

Given the peculiarities of our market, we do not expect any significant growth in attendance over historic patterns. But it is important that we retain that flexibility that we have historically, that we be allowed to fluctuate within that framework.

We have some people who would like to beat us down from that significantly, and do it on the basis of fear over fire. I understand those fears. It isn’t anything that ought to be taken lightly. But even if you calculate the potential increase to the higher end of the pattern, the total contribution to Mission Canyon traffic is only 3 to 4 percent. When you look at the raw number of 720 trips a day, that is a lot, but over the course of a day, the total traffic in Mission Canyon is about 10,000 to 11,000, so it’s not that much, particularly in terms of growth.

We will have an evacuation plan that truly makes sense and works. It’s in the interest of our neighbors in Mission Canyon and our own visitors, for crying out loud. There’s nothing else we could do that would be responsible than doing just that.

But what I also refuse to do is be scared into a corner and saying, “Well, because of the threat of fire, you have to do X, Y, and Z, and you can’t do X, Y, and Z.” That makes no sense. Let’s do things rationally. Let’s do it on the basis of existing data and on the basis of calculations we can verify — not sort of shooting from the hip.

What timeline do you expect?

If the entitlement process proceeds without significant challenge — and there’s time for back and forth — then we would expect to get approval from the city sometime in 2015. So it’s three years out, and probably late 2015. After that, all the museum has is schematic plans, so they have to be translated into fulla rchitectural plans. That takes a couple years, and then there’s the fundraising to be done. So at the most optimistic, we could perhaps begin construction in 2017. But I think that’s very optimistic.

What about costs?

We don’t have a verifiable figure, but it will be very expensive. In recent months, we sat down to see how the project could be broken up into chunks, into phases to become more do-able. That way you don’t have to raise it all in one gulp.

Would the museum have to be shut down?

There’s a good chance that, at least for some phases, the museum will have to shut down. We are a very small, compact campus, and when you do major work on one side, it affects the whole thing.

This is clearly a long-term process, yet you are retiring in the middle of it. Are you going to hang on as a special project consultant?

When I announced my retirement, there was frankly some anxiety on the board. You don’t want to suddenly have a rupture in this whole process, which is very expensive and hard enough as it is.

But in terms of my new role, what I will do the day he comes in is hand him the keys and a little piece of paper with my phone number on it, and say, “This is yours now. You are the leader. You do what you want. If you want me or need me, here is my phone number. Give me a call and I’ll be there in five minutes. But it’s your call.”