Anon(ymous), an adaptation of Homer’s The Odyssey by Naomi Iizuka.

At Westmont's Porter Theatre, Friday, February 22. Shows Feb. 29 and Mar. 1.

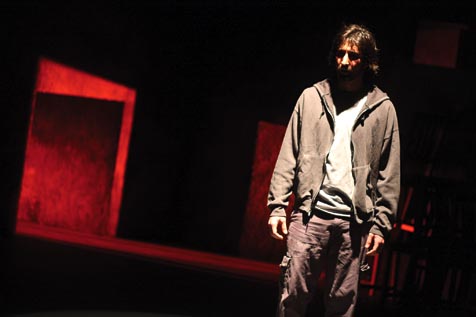

Anon(ymous) has been brilliantly directed by John Blondell in a free and dynamic post-modern idiom. It is set in the present, and its central trope is globalization. The Penelope character, Sewing Lady (Hannah Rae Moore), is a sweatshop worker, and the tapestry she unweaves at night to avoid the advances of her evil boss, Mr. Yuri Mackus (Nolan Hamlin), is both a death shroud and a T-shirt. The travels of this epic hero, Anon (Tyler Leivo), all take place within the United States, yet in many ways Anon ranges further culturally in America than his predecessor Odysseus ever did in the Mediterranean. Leivo gives a terrific performance, equal parts energy and pathos.

Even at the advanced age of 2,800, Homer’s old poem still stops often to pick up hitchhikers on its long, strange trip down the open road of history. Naomi Iizuka’s Anon(ymous) is the second stage version of the Odyssey to be crafted in Santa Barbara since 2004, the other being the more literal (but still fantastic) version by Boxtales that played at the Lobero two years ago. In contrast to the Boxtales version, which exuded the Bohemian spirit of the Santa Barbara theater guilds of the 1950s and 1960s, this Odyssey could only have come from the culture of UCSB circa 2007. Indeed, the play’s frame of reference will be so familiar to UCSB watchers that one could be forgiven for wondering when the shipping containers would arrive.

The cast has a great time with the clever, expressionistic stage business, as when rows of sweatshop workers in blue rubber gloves use synchronized hand gestures to make an ocean full of undulating waves. Their entrances through the low side apertures of Darcy Scanlin’s beautiful, abstract set often precipitate wild flights of language and virtuosic behavioral turns such as Diana Small’s Sweeney-esque butcher Zyclo and Sarah Halford’s even more striking performance as Zyclo’s excitable bird.

Iizuka clearly means to be judged on the basis of her writing, and at this point the results are mixed. Some scenes positively sizzle with verbal ingenuity, while others lapse lazily into cliche. Her white characters serve as such stereotypical villains of superficiality and evil that they seem to have wandered in from another show-perhaps MadTV. But hey, “that’s globalization, folks.”