O Superwoman

Fringe Beat

STILL INQUIRING: “Hope is a tchotchkele.” Thus saith our modern-day sage Laurie Anderson three years ago at Campbell Hall, during her beguiling solo work The End of the Moon. Back then, the sentiment’s chilling semi-truth leapt out of her long and hypnotic text, craftily wrapped up in her usual musical, digital, and sensory finery. The statement might seem even more potentially blasphemous now, in an election year when we’re high on cautious hope for the future. Of course, Anderson’s point was not to extol hopelessness, but to question preconceptions and smug assumptions.

We use the term “sage” without sarcasm or caveats: Anderson has somehow dug deeper and transformed and expanded herself in this post-9/11 age, becoming an artist who skillfully wields both the proverbial hammer and a mirror to life. Winking post-ironic humor and cool riffs are her allies. We can expect more of same when she returns to Campbell Hall on Wednesday with her latest evening-long project, Homeland-a loaded title, if ever there was one. This time, she brings a band along for the ride, with cello, bass, and keyboards.

Fortunately, Campbell Hall has been a regular way station for Anderson in recent years, during which time the artist, now 60, has produced some of the most profound work of her long, strange career. In 2002, we caught her work Happiness, in which the sound bite highlight was her adventure as a McDonald’s employee. In 2005, The End of the Moon was ostensibly an account of her gig as artist-in-residence with NASA, but it actually addressed the follies and angst of terra firma-bound humanity. Enter Homeland, which promises to be a thorny garden of earthly delights and humor-lined horrors.

Sure, we can still enjoy her fluke hit album Big Science-reissued in a 25th-anniversary package last year-and grin knowingly at her single, “O Superman.” In subsequent years, things have waxed and waned for this performance artist cum spoken-word wizardess cum singer/songwriter who can’t really sing. There have been stretches of time when her glib, too-hip-for-the-room tricks seemed tired. But that was then, and this is an expanding now.

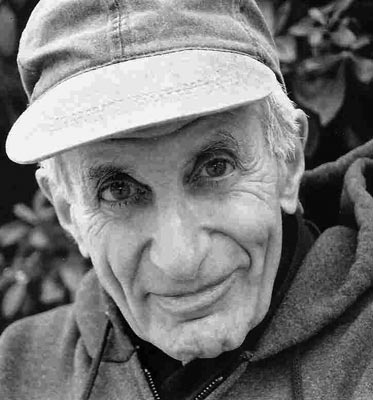

LIFE GOES ON, PART X: Composers of uncompromising “serious” music in America may be doomed (or resigned) to life outside the noisy public square of garish American life and media. Perhaps that underdog status ensures a more stress-free existence, promoting longer, happier lives. Just a thought. This year, Elliott Carter-one of finest and smartest composers in American history-turns 100. Meanwhile, on the left coast, space music composer Henry Brant is 95, and busily working. Brant has been more or less quietly living and writing on Santa Barbara’s Westside since the early ’90s. For Brant, the use of “space” is critical: He long ago abandoned music presented frontally from the stage, instead placing musicians around a given hall, spatially.

Early in his life as a Santa Barbaran, Brant’s music showed up locally, including a presentation of the memorable “Rainforest” that took place at (and around) the Lobero. He has since presented music elsewhere, globally, including his 2001, Pulitzer-winning Ice Field with the San Francisco Symphony. Another obstacle for Brant’s work is that stereo recordings don’t do justice to his multi-vantage-point music. Thus he’s had little interest in pursuing documentation of his music. Lately, though, Brant’s discography has grown dramatically, thanks to a recording series on Innova (the St. Paul-based label arm of the American Composers Forum).

Two recent volumes in the “Henry Brant Collection” offer an informative mini-survey on the now-huge Brant catalogue of works, from the whimsical to the sublime. Volume 8 showcases shorter pieces, some dating from the ’30s, with a focus on Brant’s witty-and sometimes goofy-side, including Whoopee in D, “Revenge Before Breakfast,” and some jazz-based pieces. On Volume 9, we hear a few more decidedly abstract pieces-“Dormant Craters,” “Ceremony,” and “Homeless People.” In these, we’re admittedly getting a stripped-down version of the real, spatial thing, but still, the rigor of his creative voice is intact-and captured for posterity.