25 Years Since the 23rd Olympics

A Santa Barbara Salute to the Los Angeles Summer Games of 1984

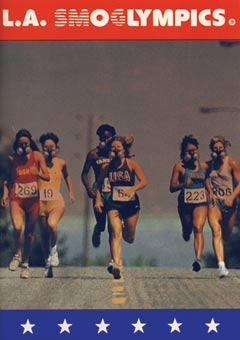

A fiasco or a fiesta? Nobody knew for certain how the 23rd Summer Olympic Games would turn out a quarter century ago. There was ample reason for pessimism. Los Angeles was the host city mainly because nobody else wanted to deal with the risks of terrorism (Munich, 1972), financial distress (Montreal, 1976), or boycotting nations (Moscow, 1980). L.A. was known for midsummer heat and smog-a distinction that a Santa Barbara entrepreneur noted when he printed up 30,000 greeting cards that displayed runners wearing gas masks beneath the banner “L.A. SMOGLYMPICS.” Inside was the message: “Gasping for the Gold.”

On July 28, 1984, the opening ceremonies at the Coliseum blew the clouds of cynicism away. If the lighting of the Olympic flame by Rafer Johnson, as pure an athlete who ever walked the earth, didn’t do it-well, the spontaneous dancing of athletes from 140 nations during the song “Reach Out and Touch Somebody’s Hand” had to do it. Above them, the skies were clear and blue.

Conditions remained ideal for 15 days of intense sporting activity. It was a coming-out party for two superior athletes from Santa Barbara: Karch Kiraly on the volleyball court and Terry Schroeder in the water polo pool. Kiraly and the U.S. spikers beat Brazil in the gold-medal match. Schroeder settled for silver by the slimmest of margins, a statistical tiebreaker that gave the water polo gold to Yugoslavia after a 5-5 draw with the Americans.

Schroeder made an artistic contribution as well. The late Robert Graham chose the water polo player as the male model for his bronze Olympic Gateway sculpture outside the Coliseum-two nude torsos (the female model was a track athlete) that will forever be a monument to the L.A. Games. Schroeder is still pursuing Olympic dreams; he was head coach of the U.S. water polo team that won another silver medal at Beijing last year.

Richard Schroeder (no relation to Terry), an unheralded swimmer from UCSB, collected a gold medal with the winning medley relay team. He finished fourth in the individual 200-meter breaststroke. On the cycling velodrome, Rory O’Reilly of Santa Barbara finished seventh in the one-kilometer time trial-despite the persistent chants of “U.S.A., U.S.A.!” the Americans did not win everything.

A retaliatory boycott by the Soviets and East Germans diminished the competition in many events, but Romania and China came to L.A. in defiance of their allies. Romania and New Zealand dominated the rowing and canoeing races that were held at Lake Casitas, a venue that gave Santa Barbara a stake in the Games. Architect Barry Berkus was appointed the commissioner of those sports, responsible for setting up the race course and spectator facilities at the lake. The athletes for those events were housed at UCSB’s dormitories. This satellite Olympic Village had an honorary mayor, Santa Barbara businessman Peter Jordano.

“It was one of the most satisfying, gratifying, wonderful times of my life,” Jordano says. He had a special connection to Peter Ueberroth, the commander-in-chief of the L.A. Games. “We both went to San Jose State,” Jordano says. “I was his ‘big brother’ when he joined my fraternity. It’s amazing how far he’s come.”

Jordano says Ueberroth made a wise choice by appointing experienced businesspeople to run the various competitions. “At other Olympics, they put former athletes at the head of the sports,” Jordano says. “It’s harder to teach an athlete to be a businessman than to have a businessman learn about a sport.” Because of the efficient organization and the use of existing facilities, the L.A. Games returned a profit of more than $220 million.

Two sports took great steps forward in 1984. Joan Benoit shattered the myth that women could not run distances as she won the first Olympic women’s marathon. Although it was ignored by U.S. television, the soccer games drew 1.4 million spectators, sowing the seeds for the World Cup to be brought to America 10 years later.

Luck played a part in the success of the L.A. Games. Temperatures never became unbearably hot. A year later, a drought had reduced the level of Lake Casitas, and a wildfire raged in the nearby hills.

But the organizers made their own luck by persuading businesses to shut down for two weeks and convincing residents to stay off the roads. The freeways were wide open, and there were no lines at Disneyland.

The day after the flame at the Coliseum was snuffed out, L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley announced: “The Games are over. Let the traffic begin.”