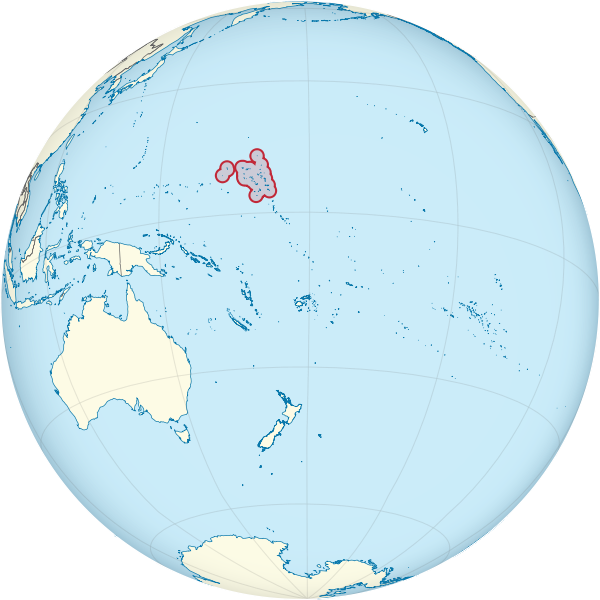

Message from the Marshall Islands

Tony de Brum Receives Nuclear Age Peace Foundation Award

This weekend, Senator Tony de Brum, from the Republic of the Marshall Islands, was given the prestigious Distinguished Peace Leadership Award from the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, for helping bring the impact of nuclear weapons on the Islands to light.

During his distinguished career in the government, De Brum has served as minister of foreign affairs, minister of health, and currently serves as minister in assistance to the president.

De Brum personally witnessed most of the detonations that took place and has worked tirelessly with international and military officials to bring closure to the Marshallese. With a new Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile test from Vandenberg AFB scheduled to impact the Islands mid-November, he spoke with us about the impact these policies have had on his people.

How have nuclear testing and U.S. nuclear policy affected the life and culture of the Marshallese people?

When you consider that the yield of the 67 weapons tested in the Marshalls was equivalent to 1.7 Hiroshima shots every day for 12 years, you can imagine the kind of social disruption that occurred because of that. When the Americans said we are going to test bombs, there were people who were very happy to give them support, especially when it was explained to them that this was going to be done for the good of all mankind; but the displacement of people and the removal of people from their ancestral homes is as traumatic an effect as that which Bravo had on me as a nine-year-old.

You lose sight of your homeland, you lose sight of your fishing grounds, you lose sight of your hunting areas, you lose sight of the places that you are familiar with, and move to a land that does not belong to you, that you don’t belong to, as we say in the islands. It is a sentence almost as heavy as any long-term prison sentence when you remove people from their islands and then tell them they can’t go back.

What do these policies say to you about the United States?

The people of the Marshalls still consider the American people to be their closest friends in this world; we’ve sacrificed, and will continue to sacrifice to live up to our part of the bargain. All we are asking is that the United States live up to its part of the bargain. If we followed the terms of the agreement that we agreed to in the first place, we would be light-years ahead of where we are now in terms of achieving what needs to be done to bring justice to the people and bring nuclear peace.

Abide by the treaties and this problem will be solved, but to stonewall something to which you have already agreed is not something that one would expect from the United States of America, the champion of freedom, democracy, and justice. What’s good for other countries should also be good for the United States.

Growing up in the Marshall Islands, what was your experience with nuclear testing?

I was nine years old, it was in the morning, and my grandfather and I were out fishing. He was throwing net and I was carrying a basket behind him when Bravo went off. Unlike previous ones, Bravo went off with a very bright flash, almost a blinding flash; bear in mind we are almost 200 miles away from ground zero. No sound, just a flash and then a force, the shock wave. I like to describe it as if you are under a glass bowl and someone poured blood over it. Everything turned red: sky, the ocean, the fish, and my grandfathers net.

People in Rongelap nowadays claim they saw the sun rising from the West. I saw the sun rising from the middle of the sky, I mean I don’t even know what direction it came from but it just covered it, it was really scary. We lived in thatch houses at that time, my grandfather and I had our own thatch house and every gecko and animal that lived in the thatch fell dead not more than a couple of days after. The military came in, sent boats ashore to run us through Geiger counters and other stuff; everybody in the village was required to go through that.

Is that the point at which you decided to become involved in activism?

I think that’s the point that my brain was taught that. I did not consciously say at the time, I am going to now be a crusader. Just a few weeks after that, my grandfather and I went to Kwajalein, where they had evacuated the people of Rongelap, where they were staying in big large green tents being treated for their nuclear burns and exposure. All the while, incidentally, the United States government was announcing that everything was OK, that there was nothing to be worried about – the denial part of nuclear testing.

What do you say to the young anti-nuclear activists you have met during this trip?

There is nothing more rewarding to me, personally, than to see understanding in the eyes of young people light up when we speak to them about this problem. To me it’s in and of itself an inspiration because we are never going to complete this work; it is going to have to be taken over by young people.

The difficulties which the United States government, the most powerful nation in the world, has had just trying to clean up what it left behind are immense and insurmountable. If the health of these people cannot be restored, the health of the community and their environment cannot be restored by the most powerful nation, the richest nation in the world, how does anyone expect the world to be able to recover from an actual war, a nuclear war? Who is going to be left to clean up, if anybody?