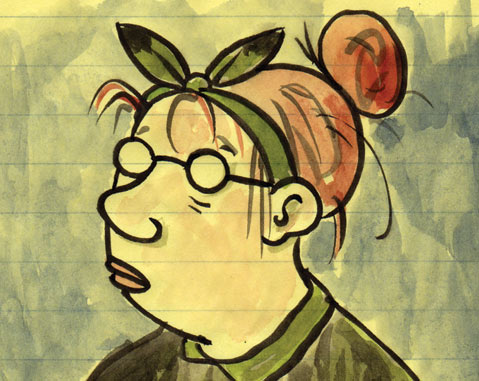

Up Close with Lynda Barry

Ernie Pook’s Comeek Mastermind Comes to UCSB

It makes perfect sense — in a perfectly weird sort of way — that there’s no Ernie Pook character to be found in Lynda’s Barry’s famous cartoon strip Ernie Pook’s Comeek, a 30-year mainstay of America’s alternative newspaper scene. Pook, it turns out, was an imaginary character created by her little brother when he was 3. “He dubbed everything he saw ‘Ernie Pook,’” Barry said in a recent interview. Years later, after Barry unveiled her signature creation — which details the harrowing adventures and misadventures of a young girl on the cusp of puberty via graphics sufficiently raw and unvarnished to induce visual splinters — she made a point to show her brother. His reaction? “He asked, ‘Who’s Ernie Pook?’” Barry said. “He had no recollection.”

For Barry, it’s always been about memories. Even though she happily retired two years ago from the weekly comic strip grind, memory still consumes her. Just differently. Well before graphic novels were invented, Barry had scratched out a niche for herself as America’s foremost folk-art cartoonist by remembering stuff many people would prefer to keep locked in their basements. There are no strong, comforting Atticus Finch father figures in her Ernie Pook universe. Maternal characters are sustained by a seething fury; above all else, they want not to be bothered.

Most of the action centers around young Marlys, left on her own to juggle the multiple and competing realities of adolescent existence, few of them happy. Leavening what could otherwise be a forbiddingly scary landscape is Barry’s outrageous humor and elliptical intelligence. But what really powers Barry’s work is her uncanny recall of the seemingly mundane — but emotionally charged — details that detonate in the reader’s brain and heart, like so many time bombs.

Barry has insisted over the years that Ernie Pook is not autobiographical, but her childhood, she said, was undeniably “difficult.” Her father left when she was 12. Her mother, a Filipina immigrant, never got over the Japanese occupation her village endured during WWII. Barry grew up in Seattle, in an immigrant family with lots of relatives crammed in tight. Little wonder her “absolute favorite” childhood comic strip was The Family Circus. “I’d look into that circle and see what looked like a really good life,” she said. Barry recalled bursting into tears when meeting Jeff Keene — who took over the Family Circus after his father Bill Keene died. “I felt like I’d crawled into that circle,” she said.

For the past two years, Barry has been teaching nonwriters—and writers, too—how to write at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. She’s drawn to the near-universal experience of preverbal toddlers to create characters, like her brother did with Ernie Pook. Her strategy is to connect even the most right-brained, educated university students with the ability to tap into that same impulse. “That, I think, is the core of the arts,” she said. “It’s our first language.”

Barry can talk about the biology of brain function with the experts; she knows that brain scans of children “at play” is akin to that of adults during “creative concentration.” Whatever you call it, Barry knows it’s essential to mental health. But she’s decidedly not about the high priesthood of art elites. (Hence admission to her upcoming talk at Campbell Hall will be free to students.) She’s all about getting even the most art-phobic to connect with their creative impulses, like the proverbial “grumpy uncle” who sings, draws, and even dances when in the company of a favored child.

To this end, Barry said, she has her students do lots of memory work. “Memory is not two dimensional,” she said. “You can get inside it. You can turn it around. You can find the light source.” She has her students get inside a memory, turn around, describe what they see and what they smell. Feelings are fine, but images are better. “It’s not about drawing perfectly,” she said. The images these exercises dredge up bring with them all kinds of memories and associations. And that’s at the core of the riddle — “What is an image?” — she’s been exploring her entire artistic life.

4•1•1:

Arts & Lectures brings Lynda Barry to UCSB’s Campbell Hall on Thursday, March 7 at 8 p.m. For tickets and info, call (805) 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.sa.ucsb.edu.