Drawing Shows by Alice Aycock and Michelle Stuart

Three Concurrent Exhibits Add Up to Much More

When museums write art history, they do so by arranging objects. Of course, there must be labels, as well, and wall cards and catalogs and lectures, but ultimately, the greatest strength of these institutions is also their biggest constraint — the stories they tell come into being through the selection and juxtaposition of actual things. In three concurrent exhibitions of important drawings now on view in Santa Barbara — two at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and one at the UCSB Art, Design & Architecture Museum — this art of juxtaposition has been raised to the highest level. By running a wonderful two-part retrospective of drawings by the sculptor and land artist Alice Aycock concurrently with an equally compelling show documenting the career of her contemporary Michelle Stuart, SBMA’s Julie Joyce has created something that’s much more than the sum of its parts. Bringing together these major retrospective exhibitions of two supremely confident and influential women artists, both of whom first reached a wide audience with major aesthetic breakthroughs in the 1970s, the SBMA and the UCSB AD&A Museum powerfully enhance the significance of each individual element of this total presentation.

Taken together, Michelle Stuart: Drawn from Nature and Alice Aycock Drawings: Some Stories Are Worth Repeating offer an alternative to more conventional art-historical accounts of the period 1970-2010 and portray a pivotal moment in the evolution of contemporary art. Building on the discoveries of such diverse precursors as Robert Smithson and Marcel Duchamp, and on an emerging sensibility derived from aesthetic globalization, Aycock and Stuart both found new, surprising, and direct ways to connect studio practice with the real world. Combined, these shows form a single blockbuster exhibition and offer a crash course in how two American women redefined the fields of drawing and sculpture, quite literally from the ground up.

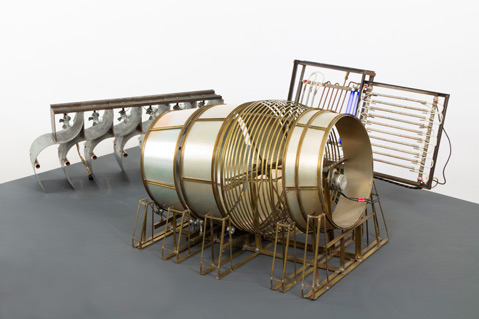

Alice Aycock got her start as an artist just as painting began to lose its grip on the collective imagination of the New York art world. Trained as a sculptor by Robert Morris at City University of New York’s Hunter College, Aycock began drawing as an ancillary to her sculptural practice and to document her extensive travel and her research in the fields of architecture, engineering, and archaeology. As a graduate student, Aycock immersed herself in the study of architecture from all over the globe, analyzing and internalizing the logic of structures created by people far removed from the conventions of Western art. Her research into the circular memorials of ancient and renaissance civilizations, begun as a project for one of Leo Steinberg’s art history classes, became the basis for some of her most important early works, including 1972’s “Maze” and the 1976 “Project for a Circular Building with Narrow Ledges for Walking.” The Aycock show at UCSB’s AD&A Museum focuses on her career up until the mid-1980s and fuses diagrams, plans, photographs, and drawings with a substantial selection of maquettes into a single thrilling experience. Beginning with relatively simple arrangements of walls and tunnels that attempt to reimagine the relationship between buildings and the land, Aycock takes a daring leap into a brave new world of impossible machines and fantastic spaces designed to baffle as well as fascinate the viewer. In these early works, Aycock merges the impulse to modify the land that she inherited from such precursors as Robert Smithson with Duchamp’s playful, highly literate approach to the limits and paradoxes of mechanical reproduction. In the AD&A show, we witness the birth of what remains Aycock’s central conceit: the artwork as an imaginary space that invites fantasy and within which nothing is impossible.

Like Aycock, Michelle Stuart began her career as a young woman with an unusual gift for drafting. Stuart, who trained at what was then known as the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, spent several years working for cartographers, turning aerial photographs into topographic maps. It was this experience that led her to redefine drawing as a form of exploration and to turn her own original art into a more comprehensive, integrated response to the land. Although Stuart’s aesthetic breakthrough began with a series of amazingly delicate and detailed moon drawings executed in 1969, her development quickly reached an initial climax with the large hanging scrolls she created by frottage on the soil of specific places, as in the iconic “#1 Woodstock NY” of 1973. By allowing this large drawing to unfurl down to and across the floor of the gallery, Stuart invaded the space of the viewer and opened the door to her earthworks, such as the magnificent “Niagara Gorge Path Relocated” of 1975. Although the relocated path, which once plunged 450 feet to the Niagara River, no longer exists, its legacy, both within Stuart’s oeuvre and beyond, endures. Like much of Stuart’s earth art, it was intended to be ephemeral, but it continues to benefit from the indelible record of photographic documentation.

At the same time that she was breaking down the barriers between drawing and sculpture, Stuart was traveling the world in search of inspiration. She found it in the Nazca lines, but she also found it in books and photographs; in the forms of nature, such as seeds; and in the forms of civilization, such as calendars and charts. As Stuart told the group of journalists who assembled for a walk-through of the exhibit last week, “the Pacific Rim is us,” referring to the entire earthquake- and volcano-ridden rim of that huge expanse of ocean that rustles constantly up against our beaches. Having spent significant time traveling to and fro on its surface, Aycock and Stuart share a passion for the beautiful, complex, and mostly unknown topography beneath.

At the SBMA, Aycock’s later career unfurls in a sweeping series of images documenting her large public commissions and her ongoing obsessions with relativity and transformation. Everything and anything can become a part of the parallel universe she constructs. From roller coasters to board games to Hindu mythology to the star charts that sometimes appear in newspapers, she feeds her appetite for imagery and concept with icons implying movement and change. Such grand installations as the 2012 “East River Roundabout” in New York City and the “Ghost Ballet for the East Bank Machineworks” of 2007 in Nashville suggest how completely Aycock has integrated the fantasy worlds of her imagination with the existing structures of 21st-century urban life. Visiting these three shows today in Santa Barbara thus becomes a kind of time travel, with the viewer moving back to the future through the innovations of the 1970s to a most liberating and expansive vision of tomorrow.

4•1•1

Alice Aycock Drawings: Some Stories Are Worth Repeating and Michelle Stuart: Drawn from Nature are both on view through April 20 at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. For more information, visit sbmuseart.org. The first part of Alice Aycock Drawings: Some Stories Are Worth Repeating is at the UCSB’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum until April 19. For more information, visit www.museum.ucsb.edu.