Macias Found Guilty of Torture and Meth Sales

Jury Deadlocked on Extortion and Kidnapping Charges

After deliberating the better part of three days, a Santa Maria jury found Raymond Macias, who law enforcement officials contend has been the county’s chief “tax” collector for the Southern California prison-based Sureño gang and a major drug dealer, guilty of torture and dealing methamphetamine. But the jurors were irreconcilably divided over allegations of kidnapping and extortion, leaving it up to prosecutor Ann Bramsen to decide whether to retry Macias on those charges.

On the kidnapping charge, the jurors split 7-to-5 in favor of guilt; on extortion, the divide was also 7-to-5. Bramsen and defense attorney Michael Scott will appear in Judge Patricia Kelly’s court next Wednesday to hash out the possibility of a retrial. Bramsen said afterward that the guilty verdicts carry a combined penalty of 23 years to life. Scott calculated it differently, reckoning the base charge of torture carries a minimum life sentence. That, he added, doesn’t include the extra time tagged on because the torture was carried out in furtherance of gang activity and that a firearm had been brandished throughout. Scott questioned the wisdom in seeking what would be another lengthy trial — this one lasted four weeks — when Macias had been successfully put away for a very long time.

Both sides agreed that Macias was nowhere present when Stephen Mendibles, a Lompoc gang member also known as Loco, had been escorted by other Lompoc gang members to a garage where he was beaten, kicked, struck twice with a hatchet, and tied up. Mendibles reportedly owed Macias $1,100 for drugs and for the taxes charged to any gang members in Santa Barbara County selling drugs as tribute to the Sureños.

Both sides also agreed that Macias arrived in the garage 90 minutes after the beating had taken place last January 3. Scott said Macias indicated he wanted to speak with Mendibles, but that he never gave any instruction that he should be kidnapped, beaten, or tortured. Bramsen insisted they’d understood his intent otherwise, and testifying on her behalf were many of the gang members who participated in the violence. In exchange for this testimony, these gang members were given lighter sentences than they might otherwise have received.

Although Macias received star billing in this trial, during which he was referred to as the “Big Homie,” he was not the only defendant. Luis Almanza, an alleged enforcer with gang ties in Texas, was accused of striking Mendibles with the hatchet — once with the flat side and once with the blade — and he was found guilty of all charges, torture and kidnapping being the most serious.

According to Scott — who, along with Bramsen, spoke briefly with jurors afterward — the jury could not agree whether Macias had intended that Mendibles be kidnapped or not. Likewise, they were divided whether he had solicited another gang member — and government informant — to extort someone else who owed Macias money. In that instance, it was the informant who contacted Macias to instigate the collection, not the other way around. But when the informant asked if he could attempt to extract more money than was owed, Macias did not object.

Scott never disputed that his client was selling drugs or that he was a gang member or tax collector. He has, however, disputed that Macias has ever been a member of the Mexican Mafia or that he in any way authorized the events that unfolded. Macias was a far cry from the ruthless criminal mastermind portrayed by the prosecution, noting that he very politely paid two “courtesy visits” to Mendibles. The situation only escalated, Scott said, after Mendibles went into hiding. And when Macias told members of Lompoc’s VLP gang he wanted to “talk” to Mendibles, he meant only that, Scott asserted.

After the trial, jurors told Scott and Bramsen that the detailed glimpse into the inner workings of gang culture proved compelling and fascinating. In closing arguments, Scott likened Mendibles’s trip to the garage — admittedly with an armed gang escort — to an unruly student’s visit to the principal’s office or perhaps to one of his own reluctant journeys to the dentist. While neither are undertaken willingly, Scott said, neither can they be called kidnapping. Mendibles went knowing that he would receive what’s called “a checking,” a beating given to gang members who violate protocol.

During the “checking,” the victim is allowed — and in fact is expected — to fight back. After a typical checking, said Scott, all parties frequently get stoned or drunk together and shake it off. This did not happen. One of the checker, Philip Lopez, had just gotten out of prison and was furious to find that Mendibles — his own cousin — had allegedly been having sex with his girlfriend while he was incarcerated. Another of the checkers — known as Little Boxer — had recently been checked by Mendibles, sustaining in the process a fractured cheek bone and broken arm.

On the January 3 checking, Mendibles quickly got the better of enforcer Almanza — also known as Lucky — putting him on his back with just one punch. He landed a solid blow on Lopez, too. At that point, gang members circling the checking jumped in. Almanza, reportedly shamed by his own poor performance, grabbed the hatched and struck Mendibles on the arm with the flat end and on his side with the blade. (While Mendibles never sought medical treatment, he testified that he’s lost full use of that arm since.) Mendibles was tied up and placed on a milk crate. Ninety minutes later, Macias showed up. According to his attorney, Macias was not informed that Almanza had used the hatchet, only that the checking had escalated to a fight. Macias cut Mendibles loose and let him go, telling him he had three days to heal. After that, Macias notified him, he would have to be poked, meaning stabbed.

Macias, insisted Scott, could not have reasonably foreseen this chain of events would have ensued because he expressed interest in talking to Mendibles. Bramsen countered that the burden of proof was not whether such an outcome was “probable” but merely “possible.” Given that there had been two gang-affiliated drug dealers murdered in North County about that time for not paying taxes, she argued, such possibilities were extremely real. Likewise, she noted that Macias had been seen speaking to his girlfriend in jail — using gang sign language — acknowledging he’d had Mendibles in his custody. As soon as Macias showed up, she argued, he was legally just as guilty of torture as everyone else who’d participated.

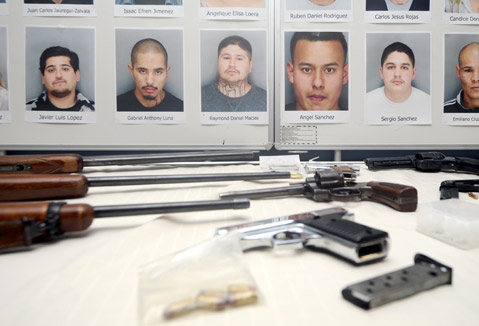

For law enforcement, last June’s arrest of Macias was cause to hold a star-studded press conference including the likes of Santa Barbara District Attorney Joyce Dudley, Sheriff Bill Brown, and Lompoc Police Chief Larry Ralston. Also on hand were agents for the FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms. Busted along with Macias were 14 North County gang members. Chief Ralston described those arrested as “the most influential top-rung drug dealers of our communities.” Ralston also described Macias as “the person that kind of calls the shots for the gang.” According to jailhouse tape recordings, Ralston’s use of the qualifier “kind of” upset Macias, who blew what sounded like an an extended raspberry in exasperated response to his authority being questioned.

Macias, however, would have to endure far worse at the hands of his own attorney during the trial. Scott — in an effort to humanize his client — suggested that Macias was a far cry from Tony Montana of Scarface fame. Macias gave deadbeat drug dealers too many second chances; with some, he paid their debts out of his own pocket. He was weak rather than brutal. Yes, Scott acknowledged Macias had wired money to accounts controlled by Mexican Mafia member Michael Moreno. But what kind of criminal mastermind, he asked, keeps receipts of such transactions in his apartment, where law enforcement could find it while executing a search warrant?

In the past year, law enforcement officials have begun sounding the alarm about the increased role they claim the Mexican Mafia is playing in area gang activities. For the North County, that’s long been seen as a given, but in the south, that’s new. The specter of the Mexican Mafia hovered over the recent trial over the City of Santa Barbara’s proposed gang injunction, with prosecuting attorney Hilary Dozer presenting an ex-Eastside shot-caller to testify that the Mexican Mafia has issued a decree that gang violence on the South Coast should be minimized because it’s bad for business.

Defense attorneys countered that the former gang member in question made a deal with law enforcement in exchange for his testimony, and they have dismissed the Mexican Mafia as a “red herring,” at least where the injunction is concerned. For serious criminals involved with the Mexican Mafia, they argued, a gang injunction would have little deterrent impact. They noted that the biggest weakness with the prosecution’s case for the injunction is that gang violence has been steadily and dramatically dropping in recent years. What better way to explain that away, the defense has suggested, than to taint that drop as part of a plot by the Mexican Mafia.

In this context, Macias makes an extremely compelling figure. Not only has he been sending money — how much exactly is uncertain, but the receipts suggested at least several hundred dollars — to a known Mexican Mafia member, but he was named one of the original 30 defendants in the city’s gang injunction as “one of the worst of the worst.” Even after charges were dropped from all but 11, Macias remained on the list. In addition, Macias has been a high-profile member of Palabra, a relative newcomer to the nonprofit community that is dedicated to reducing gang violence. Palabra is made up of a handful of older gang members who don’t feel compelled to disavow their membership so much as their violent behavior. Law enforcement has looked upon Palabra with undisguised hostility, complaining that the group refuses to tell younger gang members to renounce their own gang affiliation.

Conspicuously unlike other intervention and prevention organizations made up of ex-gangbangers, Palabra has made it a policy not to swap intel with law enforcement and instead has been quick to expose gang members they believed had been working as informants. Palabra founder J.P. Herrada said that in his experience, many of the worst gang members were police informants. Because of that status, he’s charged, law enforcement often protects those gang members who cause problems for their communities. Herrada acknowledged law enforcement had long been telling him to fire Macias, but he refused. He said he’d only get rid of Macias if and when the police department fired officers who Herrada insists are dirty.

Macias did not testify at his trial; to do so would have been tantamount to wearing a “snitch” jacket, Herrada said. Macias’s attorney concurred, explaining that Macias would have been forced to answer all kinds of questions under cross-examination by the prosecution and that so doing would put his life at risk.

That the message of nonviolence Macias spread as an employee of Palabra happened to be in sync with the Mexican Mafia’s alleged dictum was a coincidence not lost on the prosecution. Herrada, who had been active with a Goleta gang, said Macias has to take responsibility for the laws that he broke, but insisted that the prosecution twisted the facts and gave breaks to gang members far more dangerous than Macias. “And here I thought we were supposed to be the criminals,” he said.

Herrada, who testified on Macias’s behalf, said regardless of his crimes, Macias helped make the streets of Santa Barbara far safer. “Whatever Raymond did or didn’t do, he also stopped a lot of violence from happening. And when he goes away, they’ll still be safer. That’s his real legacy.”

What happens now with Palabra has yet to be seen, but Macias’s conviction will certainly hamper the nonprofit’s ability to attract grant funds.