Self-Mutating Microbes Discovered

Tiny Archaea Found to Be Able to Split Their Genes

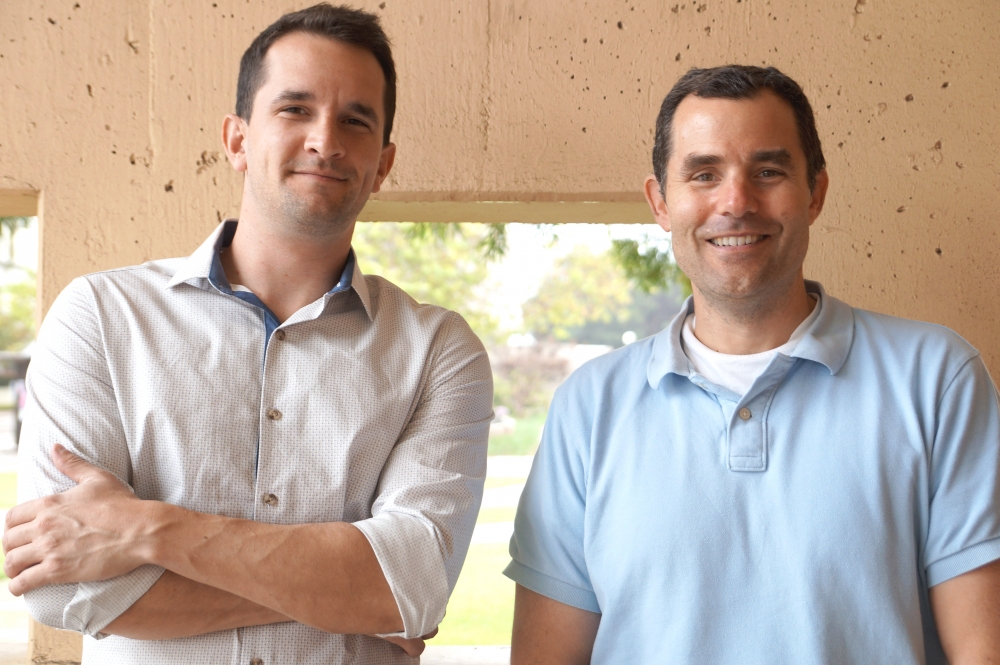

Calling them the X-men of the microscopic world, UCSB’s David Valentine and Blair Paul, and several of their colleagues, have discovered a new and populous microbe with the ability to split its genes and accelerate mutations. These tiny, single-celled creatures are some of the smallest, oldest, and most common microorganisms on Earth, and certain samples from deep waters were found to have “diversity-generating retroelements,” or genetic elements that allowed the microbes to accelerate mutations in their own genes, findings that appeared in Nature Microbiology in April.

Five hundred times smaller than E. coli, Valentine explained, these archaea and bacteria had passed through traditional filters and had also split their genetic material in a way that previously made them “invisible” to standard scientific searches. Their tiny size also led scientists to believe they evolved the ability to shed unneeded genetic material and create new ones.

Much remains to be learned about these newly identified microbes, but scientists discerned some recent mutation activity through DNA sequencing and could detect the mutation mechanism in action. Of the four DNA compounds — adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine — they saw that adenine was the component used to yield a new mutation. “This kind of basic research,” Dr. Valentine said, “has the potential to open up new avenues in health, medicine, and the environment.”

The discovery of the diversity generating retroelements led Valentine, a professor of earth and marine science, and lead author Paul, a postdoc in UCSB’s Valentine Lab, as well as their co-authors from UC Berkeley, San Diego, and Los Angeles, to search for them among other microbes. As well as deep-sea samples, they looked to an aquifer in Colorado. Not only was the mutation ability found in two classes of archaea, it appeared in some bacteria, potentially creating new, large classes of microorganisms that may receive new names.

“An important question is whether these mutations alter the proteins that the genes encode or are they meant to interrupt the genes themselves and target them for removal from the genome,” Paul said. “If this mechanism forces mutations that cause some genes to go defunct, it could be associated with evolutionary benefits.”