Invasive Tamarisk Targeted by Forest Service

Weed Spreads into Los Padres and Poses Fire Danger

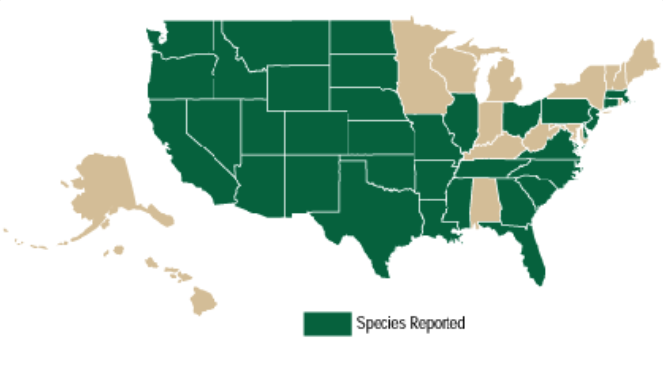

Creating a new ecosystem wherever you grow is a definite plus in the plant world. The ability of the tamarisk, also known as the saltcedar, to increase the salinity of the soil it inhabits — as well as a voracious appetite for water, deep roots, and incredible seed output — make it a great contender in outcompeting the native plants around it. Introduced from China and Russia as a windbreak tree in the early 1800s and used to fight soil erosion on the Great Plains in the 1930s, the tamarisk has spread into Los Padres National Forest, where it poses a fire danger. The Forest Service is taking public comment on two removal projects for the tamarisk, as well as other invasive noxious weeds, in Los Padres National Forest, the first of which is a pilot project involving a tamarisk-eating beetle.

The northern tamarisk beetle, also a native of China and Russia, is a “biocontrol” bug that the Riparian InVasion Research Laboratory (RIVRLab) at UC Santa Barbara, led by Dr. Tom Dudley, has been following for several years. The herbivorous insect (Diorhabda carinulata Desbrochers) consumed “visually dramatic” swaths of tamarisk (Tamarix spp.) when released in places like Utah’s Virgin River riparian ecosystem. Dense groves of the invader had supplanted the native cottonwoods and willows, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife had its eye on the willow flycatcher that nested there, first in the native trees, then in the tamarisk. The willow flycatcher has been listed as an endangered species since 1995. Something of a skirmish developed between Utah and Arizona regulators as the beetle headed south after “near-complete defoliation of [tamarisk] over large areas” in Nevada were observed. According to Dr. Dudley’s research (“Tamarisk biocontrol, endangered species risk and resolution of conflict through riparian restoration,” with Daniel Bean, International Organization for Biological Control, 2011) ultimately, fewer saltcedars led to more cottonwoods and willows, and nesting birds as well, though it took several years. Research at Nevada’s Walker River bug-release site also showed more birds returned once tamarisk had been removed.

What the Forest Service proposes is to first test the tamarisk beetle on about 250 acres in the Ojai forest affected by the 2003 Piru Fire and then to use it as part of a carefully monitored invasive-plant blitzkreig in Los Padres. Tamarisk has been found to spread fire rapidly when dry and brown — as does the reed Arundo donax — or even a healthy green, said Dr. Dudley, citing the recent research of his graduate student Gail Drus. Their presence makes a creek or river bank much less of the safety zone that green, leafy natives provide during wildfire.

When asked whether pending climate changes made a case for these competitors, Dudley replied. “The more realistic option is to use closely related genetic forms of [native] species, or within the same genus, that are already associated with warmer temperatures and/or drier conditions. Similar work is being done in Arizona with cottonwoods, testing many local genotypes of Fremont cottonwood to compare drought tolerance.” Removing plants like the tamarisk that increase soil salinity and consume more water gives native plants, and thereby native animals, a greater chance of returning and growing.

The pilot project in Ojai would be conducted by Dudley’s RIVRLab to introduce the tamarisk beetle to eat up the tamarisks — the only plant they feed on — and the second is a mechanical, chemical, and biocontrol project to remove invasive plants. Both are in the environmental assessment stage, said Lloyd Simpson, a forest botanist. Comments within the scope of the projects and with supporting reasons are due June 28. More information is available on the biocontrol project here and on the multiple controls project here.