Debt Ceiling, Bank Failures, Santa Barbara Retail Covered at Economic Talk

Economic Forecast Project 2023 Sets a Mystery About Santa Barbara's Flat-Lining Retail

Once a year, the UC Santa Barbara Economic Forecast Project musters its energies to deliver its best projections to a theater full of the navy-jacket-and-chinos crowd. At $200 a ticket — a sum equal to two days’ after-tax earnings for anyone paid minimum wage — Wednesday morning’s confab provided well-informed thoughts from a Federal Reserve board governor, the chief economist for the City of San Francisco, and the head of the university’s Economic Forecast Project: Chris Waller, Ted Egan, and Peter Rupert.

Recent economic headlines formed part of the panelists’ talks and conversation. Regarding the debt ceiling showdown ongoing in D.C., only Rupert expressed an opinion, saying it was dumb and cost the country money. He noted that similar standoffs had resulted in government shutdowns lasting from four hours to 35 days from Reagan’s time through to Trump’s.

Bank failures are the other bad news of the day. Wednesday’s conversation took place at the Granada Theatre, which is smack dab between ChaseBank and First Republic Bank, the first of which rescued the second from the jaws of failure last month. The mess on First Republic’s balance sheets was in part attributed to interest rates, which went from near zero before the pandemic to 5.25 percent today, stranding too many low-interest bonds at First Republic.

As a Fed governor, Chris Waller — who’d been a researcher for the Cleveland Fed, as had Rupert, before joining its board — discussed the data he had his eye on in determining whether or not the next meeting in June would lead to another interest rate hike. Those details included retail sales, industrial production, home manufacturing, the labor market, and so on. He was looking at their trends — rising or falling — and by how much for how long, he said.

The goal for the Fed was to adjust inflation to 2 percent, what they considered a target for an economy that was growing healthily. The means to get there was through interest rate hikes, which the governors could choose to hike, skip, or pause in June, said Waller. The choice, he said, was likely to depend on credit conditions and on how the current interest rate was affecting the various indicators.

As for the bank failures in mid-March, Waller averred the events were still too recent to reflect in the data surveys yet. Some tightening of credit had occurred since the bank takeovers by the FDIC, he said, but whether two were related was as yet unknown.

San Francisco shares some aspects of its economy with Santa Barbara, namely its tourism and to a much lesser degree its tech industry — though its population is 3.3 million compared to the City of Santa Barbara’s 87,500 — and also some of the challenges, such as high home prices and a large homeless population. Ted Egan said the pandemic caused the city’s economy to do a one-eighty, and that they’d been trying to understand what happened ever since.

The tech industry was thought to be immune to recession and inflation — but pandemic was another matter. Tech had contributed 80 percent of San Francisco’s gross domestic product, he said, but suddenly people were working from home: The stores and restaurants they’d supported downtown were suddenly without customers; the public transportation they’d ridden suddenly went unused. Homelessness became much more apparent downtown, as did empty office buildings.

What brought gasps from the audience — which held a lot of people in the real-estate industry — was the news that an office tower recently sold for 80 percent less than its pre-pandemic value, as too much office space suddenly exists. Rents were also down 15-20 percent, Egan said. And for a city with a state housing goal of 8,000 units during the next eight-year cycle, San Francisco has received building permits for only 33 units so far.

Rupert spoke last, and he managed to be both amusing and confounding. A professor of economics at UCSB, his interests include monetary economics, labor, and criminal justice. Rupert’s blog site — econsnapshot.com — contains slides similar to those he buzzed through on Wednesday, as he demonstrated that the economy, compared to years past, was on the same gently climbing trajectory as before the pandemic. Rupert noted his website, unlike some large journalistic endeavors, was accurate in its use of terms and in its interpretations. He then mercilessly dissected an inaccurate New York Times article on used car prices.

Rupert has delivered these talks for going on a decade and has clearly been educating his audience over that time. He went on to rapidly review the myriad ways to view growth — over the previous year, the past three months, the past 30 days — concluding, “To be richer, inflation has to be less than wage growth.” According to the graphs, inflation is somewhere between 3 and 7 percent, and hourly earnings — as an annualized percentage change — somewhere between 4 and 6 percent in the black. Are those roughly equal? As Rupert indicated of data percentages, the devil is in the decimal points, and apparent swings up or down could be a matter of rounding fractions.

The employee issue for many employers, from the university to the County of Santa Barbara, is that they can’t get workers to come to or stay in Santa Barbara, mostly because of the cost of housing. Thus, employment is something of an employee’s market at the moment. Compared to 2010, when each job could have five people contending for it, currently there are more jobs than people seeking employment locally, Rupert demonstrated.

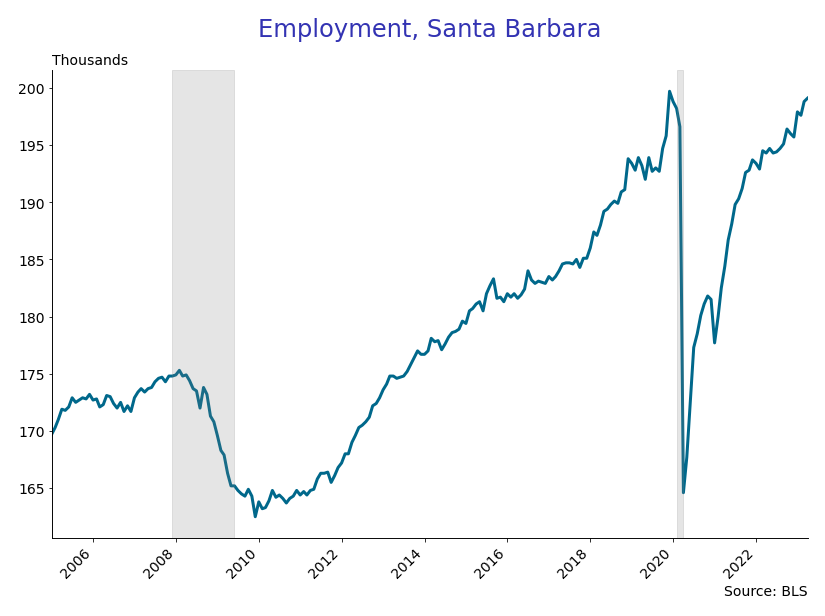

Employment data for Santa Barbara (left) and Ventura demonstrated a stark difference in retail employment since about 2000. Why Santa Barbara’s has flat-lined is a mystery. The grey bars indicate periods of recession. | Courtesy UCSB Economic Forecast Project

The employment graphs indicated Santa Barbara had a real problem. Though overall employment has reached pre-pandemic levels — but not by much — retail employment has flat-lined or staggered downward since 2000. Online sales weren’t necessarily to blame; they make up 10 percent of all U.S. retail sales, Rupert said. More starkly, he compared Santa Barbara retail to Ventura’s. Both faltered in the Great Recession and during the pandemic, but Ventura retail recovered to some extent. Santa Barbara’s did not, he said, noting the closures of large vendors like Nordstrom and Saks.

“Something fundamental happened in Santa Barbara,” said Rupert, leaving it a mystery with no immediate answer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.