The Cruise Ship Question

Is There Anything Bad About Boosting Visits to Santa Barbara?

evidence of unwanted dumping the organization’s Ben Pitterle is now making its efforts better known by calling each captain on the radio to remind them they have entered the voluntary no-dumping zone, which extends 12 miles from the City of Santa Barbara. “I really believe this is effective,” said Pitterle, “because we are present.”

Early one October morning, hours before the sun and most of California had risen, a small boat with a few bundled, coffee-sipping souls onboard skipped across invisible swells into the blank horizon. Above in the pitch-black sky, the stars shone so brightly that they didn’t twinkle, proving a brilliant contrast to the earthly streetlights of Santa Barbara, which glowed a muted yellow. But the most magical illumination suddenly came into view a few miles away on the surface of the sea, at first looking like a castle made of diamonds, but eventually emerging as the floating skyscraper that it was.

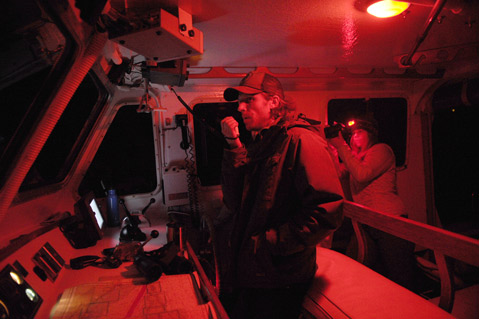

The Sapphire Princess, one of the many cruise ships that now visit Santa Barbara every year, was the early-morning target for the crew of the R/V Channelkeeper, the research vessel owned and operated by Santa Barbara Channelkeeper, a clean-water advocacy organization. The goal was to remind the Sapphire’s bridge that they’d breached the City of Santa Barbara’s 12-mile boundary and entered the zone where all cruise ship captains promise to not dump any waste. The city’s Waterfront Department set new precedent by demanding that cruise-ship captains sign that agreement — which is much stricter than the three-mile no-dumping zone demanded by state law — but the only group making sure that the ships adhere to the contract so far has been Channelkeeper, which quietly started testing the wake of the ships a few years back, recently added a thermal camera to its expanding toolkit, and is now focused on making its presence even more known.

“Sapphire Princess, Sapphire Princess, Sapphire Princess. This is R/V Channelkeeper,” beckoned Ben Pitterle, marine program director, into the radio. “We’d like to welcome you to the Santa Barbara Channel, and politely remind you that you have entered the voluntary no-discharge zone.”

“Yes, we are 100 percent aware,” replied the Sapphire’s captain immediately and pleasantly. “All of our discharges are closed and our incinerators are off.”

As the ship — a temporary vacation home for more than 2,600 people and 1,100 crew members, along with the 160,000 or so gallons of sewage generated each day — began picking up speed toward the coastline, the R/V Channelkeeper crew followed closely behind, stopping sporadically to dip empty vials into the ship’s wake and collect seawater that would be analyzed for any evidence of dumping. No one actually expects the Sapphire or other ships to violate the agreement — the consequences of being banned from Santa Barbara and enduring the ensuing marketing nightmare would be severe — and Pitterle readily admits that finding such a violation is close to impossible. “Track a cruise ship’s discharge in the middle of the night in the middle of the ocean?” asked Pitterle, as his colleagues Penny Owens and Jenna Driscoll worked on getting more samples. “It’s not an easy thing to do.”

That’s why now, as cruise ships’ presence skyrocketed to 22 visits in 2013 with nearly 30 already planned for 2014, Channelkeeper is shifting to become a visible and vocal watchdog of these floating cities, all the while balancing the overwhelming sentiment that the ships are a perfectly timed blessing for all types of commerce throughout downtown Santa Barbara and beyond. “The point is not to drive away cruise ships or the business that comes from them,” said Pitterle. “It’s more so that they know people do care about the ocean here and that we’re watching them.”

As such, Channelkeeper finds itself on the front lines of what’s quickly become one of Santa Barbara’s most talked-about developments in recent years. Right now, with a rather stunning degree of unanimity for a region rarely tepid about civic debates, the increased presence of cruise ships is getting a nearly universal thumbs-up. The enhanced tourism is good for business, in part because the Waterfront Department has handled its scheduling so strategically, restricting visits to the “shoulder seasons” of spring and fall and on otherwise slower weekdays. And even though cruise-ship visitors don’t stay in hotels, often don’t eat in town (because meals tend to be free onboard), and spend less than the average tourist, the region’s tourism boosters are gushing with excitement at the exposure Santa Barbara is getting, with high hopes that these day-trippers will come back for overnight trips in the future.

And yet even the most pro-business resident can’t help but wonder what impacts these floating cities might have on the ocean, the air, the traffic, and, perhaps one day, even the soul of Santa Barbara. Today, most seem comfortable with the frequency and function of cruise ships in our already tourist-friendly town. But in the years to come, if visits multiply as they have in recent years, will Santa Barbara ever grow weary of the massive ships dominating our shoreline?

Rise of the Cruise

Santa Barbara’s first cruise ship arrived in 2002, thanks to rising violence in Mexico that prompted the industry to rethink its West Coast offerings. “Once they started visiting other ports, especially Santa Barbara, people started responding in such a positive way that this idea of a regional itinerary really stuck,” explained the Waterfront Department’s Mick Kronman, who has been involved with organizing the visits since the beginning.

So for the next eight years, the boats — which are usually on three- to seven-day tours with additional stops in San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Ensenada — returned at the rate of about one or two per year. In 2011, in the wake of the 2009 swine-flu scare, seven cruise ships anchored here. In 2012, that number crept to 10, before more than doubling this year, with 22 visits, including the Golden Princess, the last ship of 2013, which came and left this past Tuesday. Next year, there are 29 visits tentatively scheduled, although that number was actually 34 before a few cancellations.

The steady rise is evidence of the cruise liners’ “fantastic” response to Santa Barbara, said Mike Hubbard of Quay Cruise Agencies, which books the West Coast for Princess Cruises. “It’s just a great place to go,” he said. “People seem to really enjoy it.”

Cruise liners plan itineraries far in advance, first coordinating with the U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Once it gets to the local level, Santa Barbara’s Waterfront Department is wholly in charge of evaluating, approving, and scheduling these visits, according to its director, Scott Riedman, though his staff does consult with the city administrator and relies on the help of Visit Santa Barbara (which promotes the destination), the Downtown Organization and Chamber of Commerce (which staff the hospitality desks), the Metropolitan Transit District (which handles transportation), SEA Landing (which handles the unloading and loading of tenders), and other city departments and businesses. “What differentiates Santa Barbara from so many other communities is that there is an incredible amount of collaboration,” said Kathy Janega-Dykes, head of Visit Santa Barbara. “It has really served us well.”

The Waterfront Department receives $5 a head for all people on each ship (passengers and crew, regardless of whether they disembark or not), amounting to more than $500,000, according to records from 2004 to the present. About a third of that money is dispersed to the partnering organizations to cover their costs, and the rest goes into the Waterfront Department’s enterprise fund. “We use that as needed for operating expenses and capital expenditures,” said Riedman, explaining that the cruise-ship visits do not require any extra staffing or impacts to his department.

Of course, the benefits flow much deeper into town, as well, as anyone strolling State Street, the harbor, Stearns Wharf, or the Funk Zone can readily notice on visit days. “You can tell when there’s a cruise ship in town,” reports Mayor Helene Schneider, who appreciates the strategy of scheduling the visits mostly during weekdays in the spring and fall. “That’s a big deal for the local economy.”

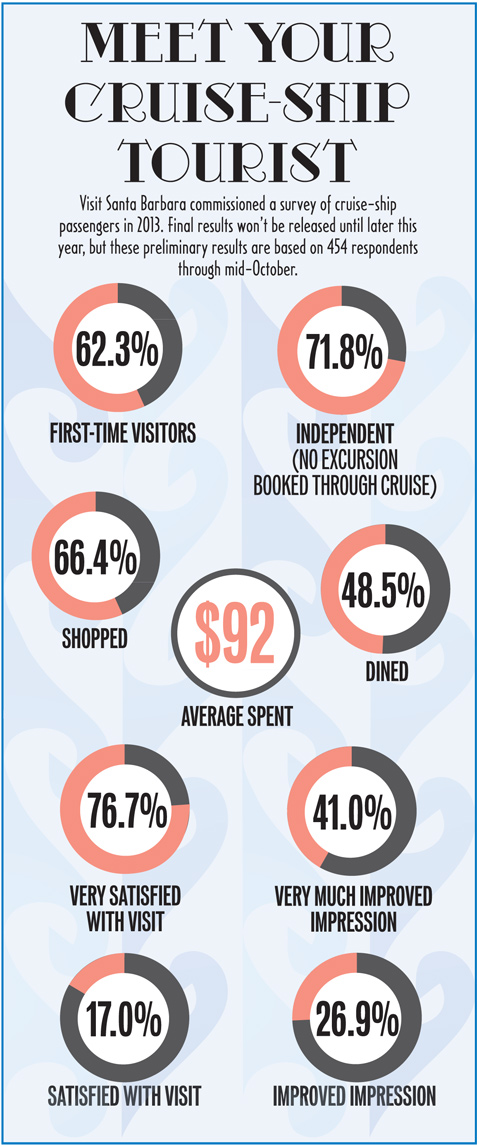

That notion is supported by the preliminary results of a cruise-passenger survey that Visit Santa Barbara commissioned for 2013. Though final results won’t be released until the end of the year, of the first 454 respondents, most were first-time Santa Barbara visitors, more than 60 percent shopped while here, just under 50 percent ate at a restaurant, and more than three-quarters were “very satisfied” with their visit. On average, they spent $92 each. (See sidebar for more statistics.)

Visit Santa Barbara’s Janega-Dykes, whose outreach was integral in attracting cruise ships here, is enthused with these early results, especially by how many are first-timers. “It is Visit Santa Barbara’s goal to bring them back again for longer stays in our lodging facilities along the South Coast,” said Janega-Dykes, who also explained that there is immeasurable value in having Santa Barbara included in the itineraries that the cruise companies send to millions of customers around the world. But the results are already tangible for businesses like Santa Barbara Trolley and winery tour guides and anyone else involved in offering shore excursions. “It’s been an amazing opportunity for many of our local businesses to work with these cruise ship passengers and provide exposure for future visits by these passengers as well as their family and friends,” she explained.

Mayor Schneider credits the hospitality tents down on Cabrillo Boulevard with making those return visits even more likely. “They are doing great,” she said. “What they’re saying is, ‘You are here for a few hours, but we want you back for a few days.’”

All Good All the Time?

So if the rise of cruise ships in Santa Barbara is like the goose that lays the golden eggs on steroids, what in the world should anyone be concerned about?

Plenty, according to Kira Redmond, who, before becoming the executive director of Santa Barbara Channelkeeper in 2004, worked for Bluewater Network to tighten environmental regulations on cruise ships at both the state and federal level. That was a major cause in the 1990s, due to whistle-blower cases against some of the major cruise lines for dumping their oil and wastewater illegally, and Redmond was eventually successful in getting California to pass stricter regulations than the rest of the country.

But problems didn’t disappear overnight, and, in 2002, the Crystal Harmony was found to be dumping 36,000 gallons of treated bilge, treated sewage, and gray water into the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, despite the captain signing a declaration, much like Santa Barbara’s, promising not to. It wasn’t technically illegal, but sanctuary officials barred the ship from ever returning and won’t be letting any Crystal ship return until 2017. [CORRECTION: The Crystal Harmony was owned by Crystal Cruises during the 2002 incident, not Carnival as was initially reported.]

When Redmond was hired by Channelkeeper in 2004, the cruise ships had just started coming to Santa Barbara, but the issue was already a topic of interest for the nonprofit’s supporters. “That was my expertise, so I looked into it,” said Redmond, who applauded the city for making the captains sign a declaration, but explained, “There was no one monitoring, so the Waterfront Department is never going to know if there was a violation unless the cruise ship company tells on itself, which is where Channelkeeper came in.”

Currently, Channelkeeper does not receive any money from the city for their efforts, though everyone asked thought that was an interesting proposition. It wouldn’t be unlike the City of Goleta paying the organization to monitor its creeks or the County of Santa Barbara funding the beach bacteria counts, except that the city’s been sued by Channelkeeper in recent years, so the bad blood lingers a bit. That said, the Waterfront Department readily shares the schedules with Channelkeeper as well as additional info, like coordinates and radio channels. Said Pitterle, “We view the city and, from what they’ve told us, they view us as partners.”

To date, Channelkeeper hasn’t caught any ships violating the agreement, and the Waterfront Department has also ensured that anything questionable gets evaluated. For instance, when a plume of smoke was visible atop one of the cruise ships a couple of months ago, the Air Pollution Control District was called to investigate. “The technician went onto the ship, into the engine room, met with the engineer, looked at all the gauges, and found the emissions to be in compliance,” said Kronman, who also had someone from the county’s Public Health Department check out a possible virus on another ship, a completely different type of environmental issue that also turned out to be a false alarm. “We take this stuff very seriously,” said Kronman.

Altogether, Redmond believes that the industry as a whole has greatly improved their environmental record over the past decade. “No question about it,” she said. “At first it was more greenwashing, but they have actually done quite a bit to improve their environmental performance.”

In agreement is David Pelkin, director of public affairs for the Cruise Lines International Association, who explained in an email that many of the industry’s practices, from their advanced wastewater-treatment systems to the gas scrubbers they use to fight air emissions, are actually “more protective” than what’s required by law. “The industry has a vested interest in protecting the global ocean environment not only because it is the responsible thing to do, but also because clean oceans and beaches are essential to the cruise experience,” said Pelkin.

Nonetheless, disasters happen — see: recent and repeated headlines about 2012’s Costa Concordia crash off the coast of Italy — and environmental violations do still occur, according to Friends of the Earth, which publishes an eco-report card on the cruise industry every year. In 2013, the cruise ships coming to Santa Barbara in 2014 posted a pretty mixed record: Princess Cruises scored a B overall, with an A for water-quality compliance and a B− in both sewage treatment and air-pollution reduction; Celebrity scored a C+, with an A for sewage and D for air pollution; and Crystal got Fs across the board. A fourth liner coming in 2014, the comparably small and ultra-luxury Azamara Quest, is not tracked.

Despite the advancements in recent years, it seems that there may still be room for improvement, at least according to Friends of the Earth, which actually took over Bluewater Network after Redmond left. “We are not outright opposed to these cruise ships coming here, but we do want to ensure that they are not having an increased impact on the channel,” said Redmond. “We want to be sure that we are present and watching, and we’re thinking and hoping that has a deterrent effect. Ideally,” she continued, “we would detect anything illicit that might happen if it did. I don’t think it will, and I hope it won’t, but we need to be out there making sure and doing the best job we can to do that.”

Aesthetic Alarm?

With business booming and the environmental concerns being cared for, the only lingering concern that may one day arise over cruise ships could be the aesthetics of having such beastly boats dominate the views of our shoreline. Though thoroughly pleased with the present state of affairs, Mayor Helene Schneider appreciates that could develop as an issue in the years to come, explaining, “If there was one there all the time, it would get a little tiring to see such a huge ship in the channel.”

It would probably be a much more pressing concern if Santa Barbara’s harbor was like its sister city, Kotor, Montenegro — where the mayor witnessed cruise ships pull right up to the dock, essentially dropping a 12-story building in town. “That shocks you,” said Schneider.

Like everyone else’s, her concerns revolve around more practical issues, like occasional cruise-related traffic on Cabrillo Boulevard and the potential for accidental spills. “The Santa Barbara Channel is a unique, special, and very biologically important place,” said the mayor. “The last thing we want to do is spoil it.”